Again the spectre raised a cry, and shook its chain and wrung its shadowy hands. "You are fettered," said Scrooge, trembling. "Tell me why?" "I wear the chain I forged in life," replied the Ghost. "I made it link by link, and yard by yard; I girded it on of my own free will, and of my own free will I wore it. Is its pattern strange to you?" This excerpt is, of course, from Charles Dickens’s A Christmas Carol where the ghost of Jacob Marley visits Ebenezer Scrooge to warm him to amend his ways. But it serves as a counterpoint to the vision that Jesus presents in the Gospel today: a vision of radical freedom. Jesus uses striking images: that his followers should be like salt, like light, or like a city on a hill. What these all have in common is that our Christian faith should change us so much that everyone else can see it. It cannot be hidden, or attributed to other sources. But at the same time, Christianity also presents itself as a set of rules, by which our behavior can be objectively judged. Some of these rules are binding upon all humanity; whereas others pertain specifically to the worship of God. The spoiler for this sermon is: you cannot get to the radical freedom Jesus proposes, unless first you have mastered the rules. As such, there are two fundamental stages to the Christian life. Sadly, some people who really want to be Christian don't get much further than the first stage, which could, somewhat indelicately, be termed 'not screwing up'. ‘Not screwing up’ is the barest minimum. ‘Not screwing up’ is the least we can do. But in order we might know for certain what the rules, are, we have the Precepts of the Church. These are the specific Catholic application of the first three of the Ten Commandments. But if ‘not screwing up’ is where your relationship with Christ begins and ends then you’re going to be constantly frustrated at the Church telling you ‘do this’ or ‘don’t do that’, and you will view the whole Gospel as impinging upon your freedom. You will begin to resent the practice of the Faith, and the only way to save face is to take for yourselves the power to judge, whether or not you are in good standing with the Church. I promise I will always tell you the truth - the hard stuff as well as the fun stuff. In the game called life it’s God who gets to decide the rules - and you have perfect freedom to choose to abide by them, or not. But you don’t get to rewrite God’s rules according to your desires. Jesus is indeed compassion and love. But he’s not on your side if you want to throw away the Ten Commandments, because they’re his, too. But this same, loving Jesus tells us both how his authority will be implemented, and the consequences if we choose to ignore it. Therefore it’s not arrogant for the clergy, ordained to act in persona Christi, to point that out, because it is revealed by God himself. These are not Fr. Clark’s rules; they are God’s rules. You are still completely free to choose to do whatever you want, but as we learn from a very early age, choices have consequences. So why does Fr. Clark insist on the rules when other priests never did? Well, quite simply Fr. Clark does’t want you to scrape into heaven by the skin of your teeth - because heaven isn’t a one and done. It’s a kingdom, with Our Lady at the top, and everyone else in order of how much they are capable of sharing the divine life. But let’s take, for example, the 3rd Commandment about keeping the Sabbath - a commandment which relates to the 1st, which is about worshiping God and God alone. The 3rd Commandment requires us to come to Mass on Sundays, which is the Christian ‘Sabbath’ since Jesus rose from the dead on the First Day of the week. Now we all love the ‘weekend’ - precisely because it makes us feel free. Unlike in the week when I have to do what my boss tells me, or what the public schools schedule tells me, at the weekend I can do what I want, and what I judge to be in my best interests. But if you’ve decided anything else is more in your best interests than worshiping God, you have, in all truthfulness, made a mistake. You see, having a ‘day of rest’ is not a natural right. It exists because secular world begrudgingly accepts that the worship of God is mandatory. We tell the secular world that we are commanded by our religion to worship God on Sundays, and because freedom of religion is part of the social contract, accommodation is made for Sunday worship. It's not the same if freedom of religion doesn't exist in your society. If you don’t believe me - consider what happened in two notable atheistic regimes. In Stalinist Russia, weekends were abolished by the principle of neprerývka or “continuous working”, and in Revolutionary France, weeks were divided into 10 days in order to disrupt the Biblical pattern and dislodge Christianity from the hearts of the people. These two examples show that the freedom of the weekend actually depends upon the 3rd Commandment. If we erode the regular practice of religion - and make it just one option among many - we should not be surprised if our day of rest is taken away. Just look to see how much we have already given away in the name of ‘working from home’. What happens when your performance review will show that you are not ‘working from home’ enough? If by your own lips you are not required to go to Mass, because Jesus won’t mind, then why are you not working? In short this can be summed up as: erode worship, erode leisure, too. Instead, we believe to choose to worship God on Sunday (in the way he asks us to, by "present[ing] your bodies, a living sacrifice" (Rom 12:1), is to choose freedom, not restraint. It’s choosing to do what you are made to do. If you do God’s will as expressed in the Commandments and Precepts, you will soar, free as a bird. If you reject them, and propose a new Jesus who simply allows you to get away with everything, you become like Jacob Marley, forging chains in your life that bind you in eternity: link by link, and yard by yard. Christ wants to offer you so much more than simple rule-keeping. St. Catherine of Siena said: ’If you find out what God wants you to do you will set the world on fire.’ She recognize the paradox that being a slave to God‘s will was in fact, perfect freedom. She became the salt of the Earth and the light of the world because she was not constantly fighting with God. We come to worship on this day because we need it, and God desires to provide it. As Gilbert Keith Chesterton said: "God made us: invented us as a man invents an engine. A car is made to run on petrol, and it would not run properly on anything else. Now God designed the human machine to run on Himself. He Himself is the fuel our spirits were designed to burn, or the food our spirits were designed to feed on. There is no other."

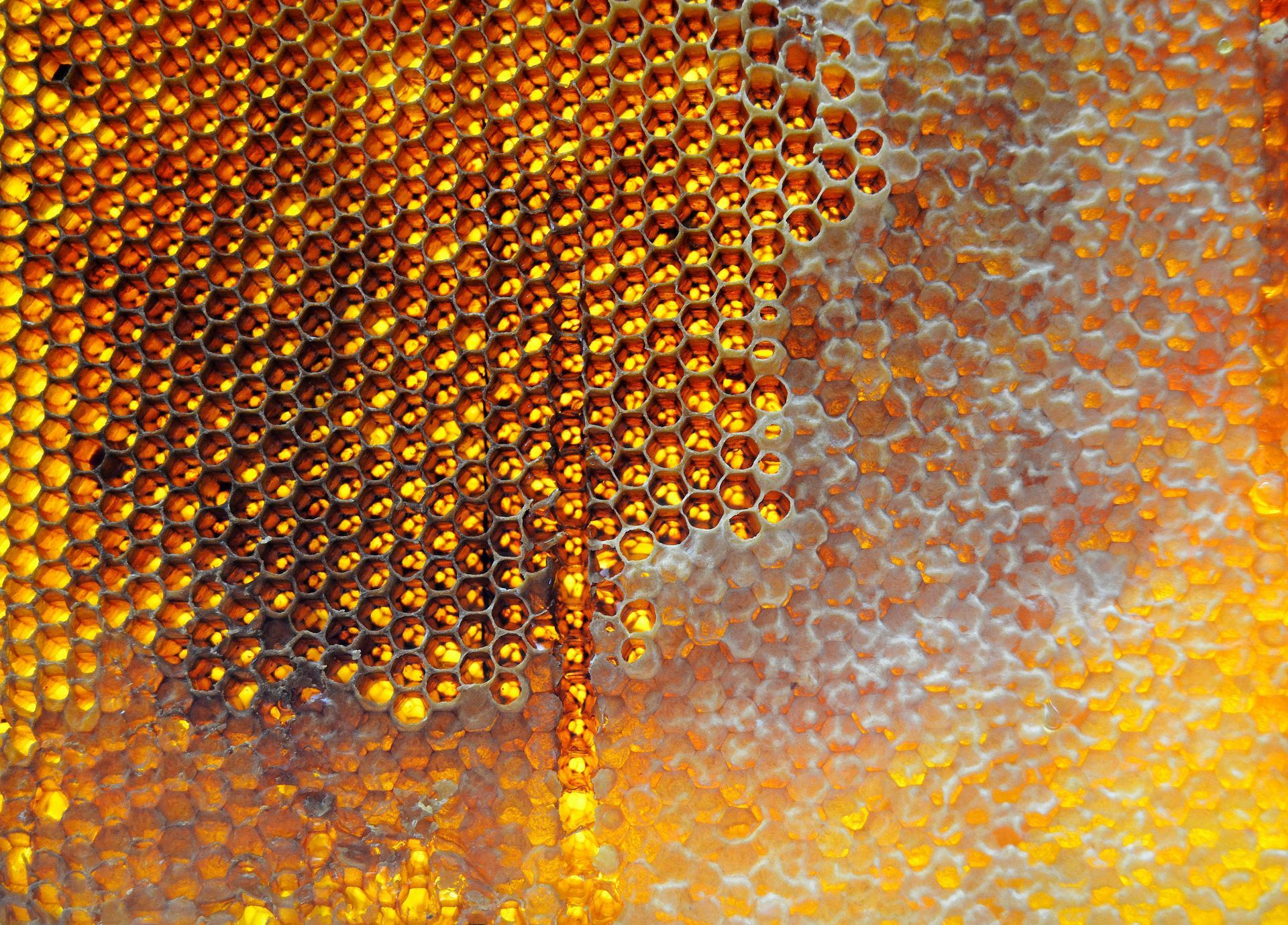

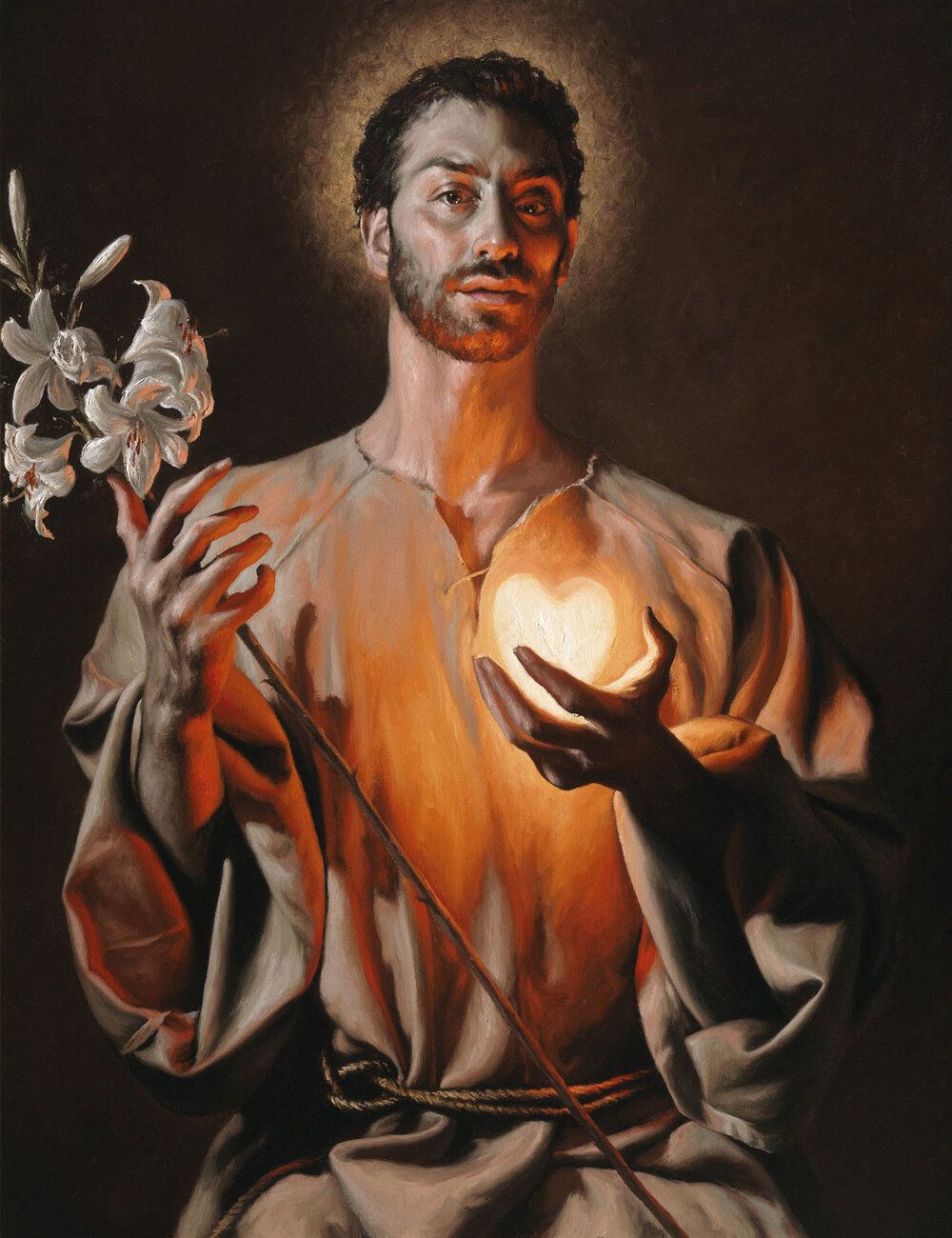

*Having been asked by one of our junior members - 'why does the Bible talk about 'bee attitudes?' Fr. Clark invited the children to guess how many bees it took to make just one of the Altar candles. The answer is 150,000 - and it represents each one's life's work. “But you’re a priest. You’re supposed to be nic e .” My agnostic sister rebukes… “I wasn’t ordained to be nice, I was ordained to be faithful” I snap back, angrily. In this spat, we’re both wrong. I’m not supposed to be nice because I’m a priest - I’m supposed to be nice because I’m a Christian - and if people are moved enough to observe I’m not being nice, then we don’t even need to move on to the question of whether I’m a good priest. I’ve fallen at the first hurdle. But let’s think about what being ‘nice’ might mean. Being nice does not mean being a wallflower: simpering, shy and retiring. It doesn’t mean being wet, or effete, either. If someone always tells you what you want to hear, and indulges your every desire, they’re actually not very nice at all: because this kind of superficial niceness is not truthful. It leaves you where you are. It actually says - I don’t care enough about you to go to the effort of correcting you. In short - you’re not worth the hassle. But we have a better vision for what being ‘nice’ looks like: it’s being prepared to die for you. That’s the ultimate standard: “ greater love has no one than this: that one might lay down his life for his friends .” (Jn. 15:13) the Lord says, and this is what he is prepared to do for us - but not just us collectively. Jesus is prepared to do this for you , even if you were the only person alive. That’s what it means to say there is no greater love than this. This choice is not a pragmatic calculation ‘if I die, then millions will be saved’: no. That’s how men think, not how God thinks. You have to acknowledge that Jesus is prepared to lay down his life for you, as if you were the only person in the world, and—that you need him to do it for you. This kind of love, self-sacrifice, is a different word from the love we have for our spouse, our family, or our friends. In many ways, it’s a shame we use the same word, love, in English, because it just doesn’t have enough power. It comes laden with the burden of emotion - and Christ’s example on the Cross is not about emotion. He doesn’t lay down his life because he thinks warm thoughts about you, or me. Quite honestly, we’re quite unloveable a lot of the time, so that wouldn’t work at all - it would make God a dope. No. The Lord lays down his life because he desires to open up a different way of living for us. A way of living that builds upon the natural law (as expressed in the Ten Commandments) and perfects it (as expressed in the Beatitudes.) It is this ‘perfecting’ of the natural law that we meet today in the Gospel. God’s moral law, the duties we owe to him, to our neighbor, and to our planet, apply to everyone, everywhere, forever. They are written upon the heart, in that evocative phrase, and they bind everyone. You must abide by them. If you do not, you rebel not just against God, but against yourself. But there is a different, and higher, law that we are called to. This law makes us look like Christ - truly earning the title: ‘Christian.’ The Beatitudes - the eight statements of blessedness that we hear Our Lord state in his famous Sermon on the Mount - are very challenging, and some are not immediately attractive: no-one would elect to be insulted, or persecuted, still less mourn, or be poor. Others we might recognize as virtuous in other people - such as being meek, being pure in heart, or being a peacemaker, but they seem so hard as to be unattainable. But although the Beatitudes do reveal a law, that law is not a set of proscriptions (do this; don’t do that) but instead a call to bear witness to Christ ever more deeply. So they are not optional guidelines, but they are not rules either [For us attorneys the Beatitudes are ius not lex. For you non-lawyers, they exemplify a binding system of justice, as opposed to giving specific norms.] The thing which unites all of the Beatitudes is refusing to compromise on Truth . So: The Poor in Spirit receive the kingdom of heaven because they know we don’t deserve it Mourners are comforted because, like God, they detest sin, and weep that his laws are disobeyed The Meek inherit the land, because they recognize all material things belong to God, not to us. Those who Hunger and Thirst for Righteousness are only satisfied by right relationship with God Those who are Merciful receive mercy they know they need it The Pure in Heart see God, because God cannot abide sin Peacemakers are truly God’s children because they cooperate with him in putting an end to division Those who are Persecuted and Insulted for Christ refuse to betray him, and thus inherit a place with him where he dwells, because they witness that what he says is true. Let’s return to my sister’s rebuke. I’ll accept it if, instead of observing I wasn’t being ‘nice’, she said: “But you’re a priest. You’re supposed to become a saint .” Absolutely. I am. And so are you. There are, after all, no ‘non-saints’ in heaven. No-one is in heaven who is not a saint. No one. Becoming a saint is hard work - and you should be relieved that already being a saint is not a requirement for those called to the priesthood, because you would have very few. I have met, perhaps, three people in my whole life I would describe as living saints. Sanctity is not to be confused with piety, which is the outward observance of rituals and traditions. I know plenty of pious people who aren’t yet saints at all, whose outward display is meant for other people to see, but whose hearts are inwardly dark and bitter. By their fruits you will know them, the Lord also says. I think one of the most refreshing aspects of Pope Francis’s pontificate was calling out this kind of behavior. He described it as rigid, and whilst I also know many pious people who are genuinely good, and working hard to become saints, for whom such words stung a little; it’s good to be stung sometimes. So someone who is really ‘nice’ is someone who bears witness to Truth, and refuses to compromise on it. It takes a thousand lifetimes of experience to distill this wisdom using our own power, but we don’t have to, because it is revealed and shown perfectly in the person of Jesus, who is the answer to everyone’s search for Truth. This uncompromising quest is best summed up the Victorian English poet, Christina Rossetti: What are heavy? sea-sand and sorrow: What are brief? today and tomorrow: What are frail? Spring blossoms and youth: What are deep ? the ocean and truth. What are heavy Christina Rossetti (1830 - 1894)

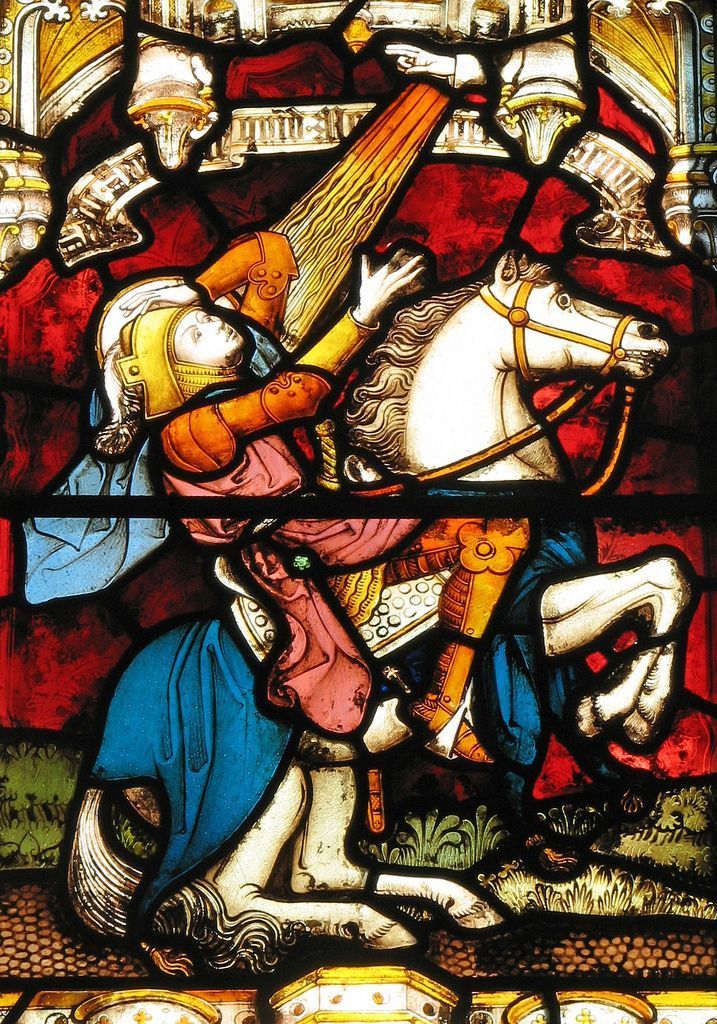

Conversion of St. Paul in St. John's College Oxford. Picture credit: Fr. Lawrence Lew OP There is no other contemporary Christian we know as well as Shaul of Tarsus, better known as St. Paul the Apostle—and we know him so well because the Church has treasured his personal correspondence from the day it was sent to the earliest communities around the Mediterranean basin. So inspiring, so heartfelt are these letter that they were copied, and distributed to others to whom they were not addressed, that they might sit at the feet of the teacher, and learn how to be a follower of Jesus. Of the thirteen documents attributed to Paul, no less than seven are undisputedly authentic - that is to say there is academic consensus that Paul, personally, composed them and sent them to churches and people he really knew. Of the others, not being ‘authentic’ does not cast a shadow on them. It means they were either written in his voice, or compiled of fragments and sayings from other letters. They all have a Pauline spirit, and together form what we call the Pauline corpus - the body of teachings that has its origin in this remarkable man. That’s all very interesting, if you like that kind of thing, but why does it matter? Well, consider how much we reveal of ourselves in our personal communications. There is an intimacy in correspondence (particularly at that time) that is not found in other kinds of writing. Compare how much more we know of the character of Marcus Tullius Cicero from his letters, to the Jewish historian, Flavius Josephus. They are unedited, emotional and raw. And because of this, they give us hope. Paul is no plaster saint. He’s right there in front of us, and unlike many others he’s not afraid to lay bare his weaknesses, because of his utter confidence in Christ. He is the primordial oversharer - and this is good for us, because it gives us hope that ordinary men and women like us can aspire to follow Christ, and being attentive to his teachings, Paul shows us the way. But Paul has come under attack, particularly in the last 50 years or so. He is attacked because his teaching is sometimes hard: he is uncompromising, and because of the power of his intellect, he is extremely clear, and persuasive. No misty arguments here. We know exactly what he means, and exactly what he expects of us. So let me be clear too - everything Paul says is correct. Everything. But to focus only on the diamond-edged precision of his teaching is to forget how remarkably compassionate and self-effacing he is too. This is an easy trap to fall into. When someone says something that is razor sharp, and clear, but we don’t like it, our first reaction is emotional - we don’t like the message, and we don’t like the messenger - and nothing else he ever says or does will lift the cloud of feeling. But Paul is uncompromising in his teaching because he is only too aware of human weakness - and very understanding of anyone who falls short of his ideals, because he admits himself he falls short of them all the time. You must then take the whole Paul, not just bits of him. When Paul first started writing (well, actually he rarely wrote himself - he had a scribe - and we know this because there are several points where he tells the recipient he has taken the pen himself and is writing in his own hand) but when he first started, it was by no means clear that we would have a New Testament at all. Remember, 1 Thessalonians is the very earliest Christian document - written possibly as early as AD 49 - sixteen years after the Passion and Resurrection of the Lord. This means there were at least sixteen years of a Gospel that was not written down - “woe to me if I do not preach the Gospel” he says in 1 Corinthians about 5 years later than 1 Thessalonians. What is he talking about? Certainly not Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John. They were at least another twenty years into the future. So it is to Paul we turn for the earliest evidence of what the Church was like - and we find it to have been even at that stage both traditional and liturgical. Traditional, because the Gospel is handed down by word of mouth, and liturgical, because e.g. in 1 Corinthians we find the first, ever recorded instance of Christians celebrating the Eucharist. Let that sink in. Paul is the first to write about the Mass - and the Mass was happening before any New Testament Scripture had been written. Liturgical, too, because Paul quotes hymns in his writings - you could say he bursts into song at points - and these hymns were expected to have been shared, and performed, with the churches he was writing to. Liturgical even more because it is Paul who writes to the churches and recalls the power of their Baptism - he assumes they already know what Baptism is, because they have received it. And no-one has ever been baptized outside of the Liturgy. Scott Hahn, the famous scripture scholar says “[T] he New Testament was a Sacrament before it was a document, according to the document .” We could say the New Testament was liturgical before it was scriptural, according to the Scriptures. Because we know Paul so well, we have in him a template of how to be authentically Christian. We cannot be Christian and set aside his teaching or example - that would be to reject Christianity, because he was a witness to Christ long before you or I were. But if the whole Church has this template, we have something even more special - we have Paul himself. You see, the Lord, in his goodness, has given us to Paul for his special concern. Being dedicated to him, means this same urgent, intense, generous, passionate saint has a special concern for what we do here - because we bear his name. It’s not that we belong to him - he himself would correct that - but since we belong to Christ, Christ has given Paul to us as patron and intercessor - and you can be sure he takes his job very seriously indeed. Bearing his name them, let me paint a picture of how a Catholic Parish should be authentically Pauline. It must be faithful, traditional, open, generous, compassionate, giving, inquisitive, and most of all, loving. But there’s one thing it can never be: casual. I don’t know if casual gets you to heaven - who am I to judge - but I do know that heaven is a kingdom, and we are not all equal there, so there is every reason while we have breath in our body to “ strive for the higher gifts ” as Paul says. Together, we have a chance in this life to grow in holiness, and that takes effort and openness to change; it takes humility, and a readiness to be taught. But let’s leave the last word to our heavenly intercessor: “ Do you not know that in a race all the runners run, but only one receives the prize? So run that you may obtain it .”

Fr. Clark gave this sermon at Evensong on January 18th for the beginning of the Week of Prayer for Christian Unity at St. Thomas Church, Fifth Avenue, New York City as guest of the Rector, the Rev. Canon Carl Turner. Fr. Clark and Canon Turner are pictured above. I’m waiting for a call from Rome. I’m sure it’s coming any day now, and the Pope will say to me: ‘Fr. Clark, you’re doing such a great job, I’m going to appoint you as Prefect of the Dicastery for Promoting Christian Unity. I think my first act will be to choose a new motto. I’m not even sure if the DCPU has one already, but it should. But since a motto is part of heraldry - you guessed it - there are lots of rules, so we need to proceed with caution. [I’m sure my brothers and sisters of the clergy could offer some helpful suggestions, but I probably can’t repeat them here.] Best to stick to Scripture. Fortunately our Second Lesson tonight provides the perfect text for the motto, from the Lord’s own lips: tí pròs sé . What’s it to you? But let us understand one thing very clearly about these three little words: it is a rebuke - and it was issued to Peter just moments after the Lord gave him pastoral charge over the flock. The same Peter, whose confession of Faith at Caesarea Philippi remains a point of unity for all Christians, is rebuked at the very moment his eyes are not fixed upon his relationship with Christ, but upon someone else’s relationship with Christ. It’s important to observe two things about this passage: first, we only know about it because Peter was content for it to be shared - indeed, the author of record is the ‘someone else’ Peter was enquiring about, namely John the Beloved Disciple, who is clearly anxious to correct the rumor that the Lord said he would never die. Even though it isn’t a flattering portrayal of Peter, it’s an important one, because it teaches us the futility of comparing our relationship with Christ to another’s. We must also take heed of the fact that Peter’s temptation occurs after he has turned around. The text is very clear: epistraphèis ho Pétros - Peter, having turned around, or ‘turning about’ as we heard proclaimed, sees John, and switches his attention from the Lord and onto the disciple the Lord loves. So we are particularly susceptible to this temptation to comparison after we have turned to Christ: and therein we see the first seeds of disunity that the Evil One wishes to sow amongst the brethren. Instead of a vertical relationship with the Lord, Peter looks to the horizontal - what about him, Lord? In this Week of Prayer for Christian Unity, it is worth pausing to reflect on how far we have come on this journey together - polemic between Christians tends to be reserved these days for social media (God forgive us) and not official channels but there is still much more to do, so let me offer tonight three areas for further reflection: The first is, to insist upon the vertical dimension with Christ and not the horizontal. Fix our eyes upon him and him alone, so when we quibble to the Lord about our brothers and sisters (whether within or without our own church communions,) let us hear him say: tí pròs sé - what’s it to you? So what if their pathway is different from yours? Instead, follow me. The second is, to recognize that things that are important to us are emotional, but emotion is not always the best barometer of progress. A good example of this concerns Holy Communion. Whenever I attend the Divine Liturgy in an Eastern Orthodox church, I am not invited to concelebrate, nor to receive Holy Communion. There’s a sadness in that, and it’s certainly emotional; but if I dwell on the externals, I fail to see the high degree of communion I already share with my Orthodox brethren. So when we feel despondent: again, let us hear him say: tí pròs sé - what’s it to you? Are you not able to offer me a sacrifice of praise all the same? Are you not able to present your body a holy, living sacrifice? Of course you are. Instead, follow me. Thirdly, and finally, to move from respect for one another’s traditions to reverence for them. God desires legitimate diversity: he does not insist that we all worship him in identical ways. Our unity is not expressed with a liturgical cookie cutter, nor a theological one - and it is through our differences that God can show himself to us to in the other. We need only look to the noble tradition of choral excellence, for which this church is justly famous, as an example of the gold that God is able to create, even out of canonical division. So, if someone prays or expresses themselves in a different way to us: again, let us hear him say: tí pròs sé - what’s it to you? Do they not come even from Sheba and Seba bearing gifts? They absolutely do. Instead, follow me.

Have you noticed we have moved at liturgical lightning speed in just a week? Faster, in fact! Last Sunday, we were at the manger with the Magi, this week we come to the Jordan River, where the Lord is all grown up. Or rather, as Luke tells us, he “advanced in wisdom, and maturity, and favor before God and man” (Lk 1:52.) And he comes to be baptized by John the Baptist. Wait, a moment. He comes to be baptized? He advanced in wisdom? And favor with God? I thought you said this was the Word made Flesh, God with us? Why does he need to be baptized? How can he advance in wisdom if he is the source of wisdom itself? How can he grow in favor with God, if he is God? These are all excellent objections - and they are precisely what we see in John’s reluctance to baptize the Lord: John tried to prevent him, saying, “I need to be baptized by you, and yet you are coming to me?” The Baptism of Jesus is more than merely a historical record. The fact the Lord chooses to perform this sign means he wants us to know something. Now, we could just pass it over, shrug our collective shoulders and say ‘I dunno’…or we can delve into the mystery, and discover the sparkling beauty of God’s plan for us. First, let’s recall the background. Remember, in Advent, we agreed that John’s Baptism was the precursor to the Sacrament of Penance (also known as Confession) rather than the precursor to the Sacrament of Baptism. We also concluded that John’s Baptism was an interior recollection - a desire for a fresh start with God - journeying in to the desert, a ritual dying to sin, and being reborn.But it always pointed forward to something greater. As the Baptist himself said: I baptize you with water for repentance, but he who is coming after me is mightier than I, whose sandals I am not worthy to carry. He will baptize you with the Holy Spirit and fire. (Mt 3:11) Now, Jesus, who is perfect and sinless by nature, has taken upon himself our humanity. God has clothed himself with flesh and now dwells among us. His humanity is not wounded by sin, but ours is, and Jesus is the only way that mankind can be reconciled to God, because only his sinless sacrifice could ever be acceptable to the Father. So in submitting to John’s Baptism Jesus is really putting a definitive end to it, inaugurating a new Baptism into his body - the Baptism that you and I enjoy - that will be practiced by his coworkers, the Apostles, because of the commission Jesus will give to them to baptize all nations in the name of the Father, Son and Holy Spirit. He enters the waters to fulfill all righteousness: to stand in solidarity with us, even though we don’t deserve it, and to bring John’s preparatory baptism to its fulfillment. In that very moment, the old yields to the new. Secondly, let’s consider the deeper typology. Baptism is a symbolic death - the Hebrew people were culturally fearful of water - they were a pastoral people, not a seafaring people: the sea, and its chaos was something to keep at arm’s length. As an aside we see remnants of this in the early Church - the book of Revelation describes the new heaven and new earth as a place without a sea: something which my naval officer father will definitely have to learn how to appreciate. If the sea is dangerous, and the waves are frightening, then going underwater is a metaphor for death - and rightly so. By submitting to John’s Baptism, Christ is not signifying his need for repentance at all, but he is pointing to a different sign - that he will have to die in order to save his people from their sins. It was John, after all, that recognized that Christ is the Lamb of God. Almost nonchalantly, he points to the Lord from afar with words we recall at every Mass: ecce Agnus Dei! Behold the Lamb of God! John’s disciples knew what that implied. The Lamb is always the sign of sacrifice, from Abraham and Isaac to the blood smeared on the Passover doorposts - the spotless Lamb is born to be slain, and therefore the symbolism of the Lamb descending into the waters was even clearer to those who witnessed it than (perhaps) it is for us. But thirdly, what about advancing in wisdom, and stature, and favor with God? How do we begin to deal with that? Well, we confess that Christ is true God and true man. Not a hologram, or a chimaera. As true man, he chose to experience a defining characteristic for all of us: growing up. It stands to reason that a baby is innocent, but a baby needs to grow…Christ in the manger is all-beautiful, but he cannot preach or teach (at least not with words.) It is his sinless humanity that may advance in wisdom, and stature, and even grace. But remember this - he is at the same time the one who receives this growth, and the one who gives it. The source of his wisdom, and stature, and favor, is the divine life itself, which he shares in the communion of the Holy Trinity before all worlds. St. Cyril of Alexandria helps make sense of this interplay: “ God the Word gradually manifested His wisdom proportionably to the age which the body had attained .” The divine wisdom was not lacking; rather, in the economy of the Incarnation, it was revealed step by step, according to the Lord’s human nature’s capacity to receive it—so that we might recognize Him as truly one of us. The Baptism of Christ is that point of recognition. We see him clearly now. For thirty years, in the hidden life of Nazareth with Mary and Joseph, the Lord’s humanity has grown in stature both body and soul. At this point of his life on earth, he is ready to reveal to the world his anointing with the Holy Spirit, and his favor with God the Father. This is why the Baptism is also a form of epiphany - a manifestation of something we need to know and understand about Jesus. But the revelation of his anointing is not simply for us to marvel at the Godhead. At two points in the Gospel of John, Jesus reveals himself as a wellspring of living water; a source which when we partake of it, becomes a spring in us for others to draw upon. This divine life was imparted to be shared - the living water is the action of grace by the Holy Spirit, that is applied to us because the Lamb of God renders a perfect sacrifice to the Father. He is the one to hand over that life! Just as he hands it over to the Father at Calvary, he hands it over to us in the Sacraments. You see, the water alone is not sufficient, we need the water and the blood. Indeed the water only makes sense because of the blood. If you drink deeply from this fountain there will be a moment of manifestation, of showing forth, for you - your hidden life will bubble up, and bubble over with living water. Your own trials, frustrations, and sufferings are precisely the Jordan River for you. Imitate Christ in prayer and holiness and you will rise with him from those waters of strife, and advance in wisdom, maturity and favor with God and men.

Most sermons on the Epiphany focus on the mysterious visitors from the East, or the three enigmatic gifts they bring. For good reasons - in them, we find ourselves, as foreigners come to worship the King of the Jews, and in their gifts, we find the meaning of his Incarnation: he comes as king (signified by the gold;) he comes as God (signified by the frankincense;) and he comes to die (signified by the myrrh.) That’s a summary of the content of most Epiphany sermons. But today I want to focus on Herod , who is often passed over in the narrative, or reduced to a mere pantomime ‘baddie’ at whose very name you should enthusiastically cry: ‘boo.’ In the scheme of things, Herod is a baddie - he is both a liar and a tyrant, who sets himself against God’s plan because he feels intimidated by its consequences for himself and his personal prestige. But when we reduce him to the comical figure of a clown, we fail to notice the ‘Herod’ in all of us, and, how our response to the Star is not always the trusting faith of the Magi. Herod is thus an intriguingly contemporary figure. He has everything he wants, and much more than he needs: he has money, power, and prestige. He lives a life of exceptional comfort in multiple palaces, with wine, women, and song. But there's a reason for his success: He’s a skilled politician and military leader, earning the respect of the Roman authorities. And yet he’s cruel, envious, and insecure. You need to know a bit of historical background to understand Herod and his dynastic ambition, and to understand why Israel had such a strong Messianic expectation at this point in history. It's not very well known, so please indulge me in a history lesson. In the century and half before the birth of Christ, something extraordinary happened: Israel, under the Hasmonean priestly kings, managed to throw off the shackles of foreign domination, and establish its own empire - conquering territory, and destroying old enemies, like the Samaritans, whose rival Temple at Mount Gerizim was razed to the ground by King John Hyrcanus in 110 BC. But this successful Jewish kingdom hit the buffers in 63 BC because of a succession crisis, and the rival claimants appealed to Rome for help. They got a different kind of help from what they hoped to receive - on the orders of Caesar Pompey marched south to Jerusalem, laid siege to the Temple, eventually overcoming and defiling even the Holy of Holies. The Romans would not leave Judea for centuries afterwards. Herod was a young boy when all this happened, and his later rise to power happened because he knew how to curry favor with Rome. He was an Edomite - a race of non-Jewish people to the South who were forcibly converted by the Hasmoneans - and viewed with suspicion by the priestly class in Jerusalem ever since. Their Jewish status was always ambivalent - and we can see from the Gospel that Herod is pretty ignorant of Scripture. Having been proclaimed King of the Jews by Mark Antony and the Roman Senate, in Rome itself, in 40 BC; three years later, Herod deposed the last Hasmonean king in 37 BC, and began his rule as client king for Rome which lasted 41 years until AD 4. He was an old man by the time Christ was born. But it is the story of his encounter with the Magi, and his bloodthirsty Massacre of the Innocents for which he is remembered in history. In his Epiphany sermon of 2011, Pope Benedict XVI, with his trademark precision, identifies Herod’s catastrophic failing: he sees God as a rival: God also seemed a rival to him, a particularly dangerous rival who would like to deprive men of their vital space, their autonomy, their power; a rival who points out the way to take in life and thus prevents one from doing what one likes. But the truth is Herod’s freedom was always an illusion, because it depended upon his usefulness to a higher power - the Emperor. For as long as Herod kept order in Judea, Rome would tolerate his pomp and cruelty. But the background to the Magi’s arrival showed just how brittle Herod’s position was, and it should remind us how brittle our own illusions of security are. By supernatural signs in the heavens, God revealed to the Magi, also outsiders, that the true King of the Jews had been born. The one whose claim to kingship was no political expediency, nor military victory, but literally written in the stars. How Herod's blood must have run cold when he realized that the supernatural sign confirmed the Scriptural prophecy of the Messiah’s birth in Bethlehem. But God is never a rival to us. He does not come to take away our freedom. He insists on worship, not for his own aggrandizement or amusement, but because it makes us better. His coming into the world forces us to change, but he also shows us the way. The Magi show us that Christ’s call to humanity is universal - and we are only excluded if we chose to exclude ourselves. Encountering Christ in the arms of his mother means we have to let go of the petty kingdoms we so easily create. We have to recognize that all we have (money, prestige, intelligence, good looks - whatever it may be) comes from God and belongs to God. We have nothing of ourselves for which we are truly responsible except our sins. The Magi learnt this on the lonely silk road, but, like them, in Christ we have another way (a short cut) by which we should return home. As Chesterton observed: Oh, we have learnt to peer and pore On tortured puzzles from our youth, We know all labyrinthine lore, We are the three wise men of yore, And we know all things but the truth. If like Herod, we choose to make God a rival, then this other way is barred to us. So instead let us hurry to Bethlehem, brimming over with joy. Let us like the Magi enter the house . But let us leave the Herod within us outside in the cold - our paranoia, our need for control and our reliance upon ourselves. God has no desire to make us an enemy, he comes as child; innocent and vulnerable, inviting us to seek ourselves in his sweet eyes. So let us surrender our weapons at the Manger and see how he will turn them into gold. Let us choose the Star, and not the throne.

For this reason I bend my knees to the Father, from whom every family in heaven and on earth is named, that according to the riches of his glory he may grant you to be strengthened with power through his Spirit in your inner being, so that Christ may dwell in your hearts through faith… Eph 3:14-17 This, my friends, is the blueprint as to why the Holy Family is so important to our understanding of Christian discipleship: for in these verses we hear three reasons why the family we celebrate today is called holy - (1.) because it honors God the Father, (2.) because grace abounds in it, and (3.) because Christ dwells there. These three components elevate a natural institution into a supernatural one, and the key to all of it, is grace . There is a danger, you see, with an icon of the Holy Family. Composed as it is of the Incarnate Word, the Immaculate Conception, and St. Joseph: holiness is not simply something this family aspires to, but rather it is intrinsic to the communion they share with one another. Similarly, the flow of authority in the Holy Family is reversed. We hear in Colossians the proper order of things in natural families - whereas, at least as far as his divinity is concerned, in the Holy Family, the infant is the source of all authority, power, and grace. We may draw inspiration from gazing upon the Holy Family, but we must firmly resist any temptation to imagine that our own families could ever be holy in the same way or by the same title. The House of Nazareth is not a blueprint for direct replication; it is a unique, divine-human communion whose holiness is intrinsic, immediate, and inseparable from the presence of the Incarnate Word and the singular privileges granted to its members. Our families, composed entirely of fallen human persons, can never claim such holiness by nature or by right. The Holy Family, you see, is rooted in grace, and grounded in obedience to the will of the Heavenly Father, and thus its holiness depends directly and immediately upon the holiness of God, and the holiness of God is characterized by the outpouring of love between the three persons of the Trinity. The insight of the Holy Family for us is the presence of Jesus , the mediator and advocate, in such a concrete and tangible way that you and I can begin to relate to him as Mary and Joseph did. We know, of course, that the Blessed Virgin is the Immaculate Conception, and thus full of grace (literally, the already-graced one) and Christ is also described as full of grace and truth - which, you must understand, relates to his humanity, which enjoys the fullness of grace because it is united to his divinity. So what of St. Joseph? Well I know you will be hosting your Theological Cocktail Parties this Christmas week, perhaps a fun question over the martinis might be: when is St. Joseph redeemed? The Bible does not tell us explicitly, in the way it does Our Lady, St. John the Baptist, St. Elizabeth, and even the Prophet Jeremiah. But by simple logic, he must have been: for two reasons. First, he is righteous, and God shares details of his plan of salvation with him, and secondly, his marriage to Mary, although it does not involve natural marital relations at any stage, is indeed a true marriage, and thus St. Joseph is granted authority over Our Lord in his infancy. Indeed, Luke tells us directly: “he was obedient to them” (Lk 2:51.) There is simply no way that the Lord, in his humanity, could ever be obedient to anyone who was not full of grace - so, at some stage, Joseph, like Mary, also enjoys the preemptive application of the merits of Jesus Christ, by special privilege. Let us be precise about the grace at work here. Sanctifying grace is that substance by which the divine life dwells in the soul, making it holy and pleasing to Him. In the Holy Family, this grace was present in an utterly singular way: In Christ, by the hypostatic union — His human soul enjoyed the vision of God and the fullness of grace from the first moment of conception, by virtue of his divine personhood. In Mary, by the Immaculate Conception — preserved from all stain of original sin and filled with grace in anticipation of her Son's merits. In Joseph, we deduce, by a special and extraordinary privilege — cleansed, elevated, and filled with grace (as his righteousness, his intimate sharing in the mysteries of salvation, and the obedience owed him by the sinless Christ all demand). Thus, the holiness of the Holy Family did not depend on Sacraments; it flowed directly from the presence of Jesus and the preemptive application of His future merits. Their home was holy because God Himself dwelt there in the flesh, and His grace overflowed immediately into Mary and Joseph. Our families receive sanctifying grace in a different manner: not intrinsically, not by special preemptive privilege, but through the Sacraments, instituted by Christ after His Passion and Resurrection. This is the presence of Jesus for us in our families. Baptism imparts the initial indwelling of the Trinity; the Eucharist sustains and increases it; Penance restores it when lost; Matrimony and Holy Orders confer graces specific to states of life. Without these channels, our souls remain in the poverty of fallen nature. With them, the very same merits that sanctified Nazareth in advance of Calvary are now poured out upon us — not because we deserve it, but because Christ has opened the floodgates of grace through His Church. So if the Holy Family is so far removed from our experience, so far above us, as to be beyond our grasp, what hope is there for us? A good question, with a beautiful answer: the merits of Jesus Christ which were made available to the Lord’s family before his Saving Passion, are now freely available to you and me! It was already by Christ’s power that the Holy Family of Nazareth was and remained holy, and it is by that same power, because of the superabundance of his love for us, that he wishes for your family and mine to be joined to his through the application of the merits of his Cross. Therefore, to keep your family holy, you need to carry your family to his! The Christchild you see lying in the manger is present in time and space, for a little while only; but that same Christchild is available for you to take home, here today in the Eucharist that he instituted the night before he died. The Christ who made Nazareth holy by His mere presence now makes your family holy by His real presence in the Eucharist, and by the sanctifying grace He bestows through every valid Sacrament. There is no other way. Only the Sacraments — the ordinary, instituted means — bring the merits of the Passion into your home, into your marriage, into your children, transforming your natural family into a supernaturally enriched one: a domestic church. You can’t do it without the Sacraments, because you can’t do it without Him ; and He who was rich became poor and dwelt among us precisely that our poverty might be transformed by the extravagance of his gift of himself to us. My friends, do not leave this church today without resolving to bring your family more frequently to the sources of grace that are freely available to you at any moment. That is how the riches of Nazareth truly become yours.

I’m a risk taker by nature. It’s in my personality. If I see a third rail, I’ll jump on it. Looking out at the congregation in Greenwich, CT I daresay I’m in good company. Now, if you’re not so familiar with the inner workings of a Catholic parish, the Christmas Pageant is probably “third rail ++” here at St. Paul’s, sitting as it does at the intersection of 'Christmas traditions' with 'Glenville moms.' So I rewrote the Pageant. All of it , and my aim in doing so was to be faithful to the Bible story, and in particular the dialogue. I wanted Gabriel to say the actual words to Mary, and for her to respond: I am the handmaid of the Lord . So the Little Drummer Boy had to go. Out he went - of all the stretches I might have tolerated - no. Not him. He didn’t make the cut. “ Father, we need to talk about the Pageant… ” The call came later that night. Oh dear. Come back, Little Drummer Boy! All is forgiven… Thank God they didn’t know I was this close to removing the Innkeeper - and the Inn. That’s right. Here’s the first time 'Father Grinch' can steal your Christmas by telling you - there was almost certainly no Inn, and Our Lady and St. Joseph were not wandering refugees looking for board and lodging (at least not that night, in that place.) “ And she brought forth her firstborn son and wrapped him in swaddling clothes, and laid him in a manger, because there was no room for them in the inn .” So familiar isn't it? As familiar as pageants, tinsel, angels, and presents. The whole heavy lift of our wonderful Christmas traditions. But if we leave Christianity behind in our childhood, with the candy canes and the fairy lights, we will never discover a religion far deeper, and more sophisticated, than we might ever know. If there’s only one thing you remember from my sermon this year it is this: look again at the Faith you think you know . Come with me a moment - and let’s revisit the Inn. The word Luke uses in 2:7 is fascinating, and deliberate. Not no room for them in the inn , but instead, no place for them in the katalýma . Luke uses this word, katalýma , only twice in his Gospel; (when you see a word only once in the Bible, it’s a red flashing light; when you see a word used only twice, it’s a five-alarm fire,) Katalýma you see does not chiefly mean 'inn' - it means guest room, or lodging place. Somewhere set apart for visitors. It’s not actually the word Luke uses for ‘inn’ - remember, the parable of the Good Samaritan? It is only found in Luke - and there he uses the word, ‘ pandochíon ’ for a wayside establishment for itinerant travelers. Luke uses a different word to describe: (a.) the guestroom in Bethlehem, where there was no space or privacy to give birth to a child, and, (.b) the upper room in Jerusalem, where this child, once laid in a feeding trough, would go on to feed his followers with his own flesh, by his own hand. Katalýma , then, is best translated as ‘upper room’ and not ‘inn' - it is related to the Greek verb for loosening, or throwing down, and you can imagine the first thing your visitors do when you receive them into your home is to throw down their belongings. This all makes so much more sense when you consider the wider historical context. Remember, our religion is a Middle Eastern one, and we may have some work to do to reconstruct Middle Eastern social customs that are implicit in the sacred texts. Joseph and Mary have traveled to Bethlehem, because it is Joseph’s hometown; he is from Bethlehem. It is thus inconceivable that a family member would travel to their hometown and not stay in the family home, particularly when we know that Joseph is of the house and line of David, and is coming home to David’s city. We don’t know the reasons why the upper room had no place for them. Perhaps the house was full to bursting? Or perhaps the Blessed Virgin retreated to the only space left she could give birth in peace and privacy, but what we do know is that the Lord did not enter into the upper room that night. Not yet. But one day he would. This is the strangeness of our faith. Christianity isn't a tidy story of a heartless innkeeper or a sentimental stable scene. It's wilder, and more paradoxical: the infinite God contained in a tiny body: the vulnerable one who is invincible, the victim who is a victor, accessible, yet still unapproachable. You see, what Christmas begins - the upper room completes. There, finally, this child will take bread and wine and say, " This is my body, given for you. " That upper room is truly a place of loosening, or throwing down, because it is here the saving act of Calvary is given as gift to us. Through the Eucharist, Death flees away and life enters in. This is the great exchange - we bring not gold or frankincense, but our broken hearts, our burdens and we lay them at the Altar of the manger, upon the sinless body of this innocent babe. And he in return, will break this tiny body for us on the Cross, and share all he has with us, even though we do not deserve it. So if you cannot love him for his Cross, you must love him for his Crib, for they are one and the same. What Christmas begins - the upper room completes.

If you haven’t ever read Pope Benedict XVI’s addendum to his seminal work, Jesus of Nazareth, called The Infancy Narratives - go out and buy it now. It could even be under your tree by Wednesday night. Beautifully translated from the original German by my own seminary rector no less, it is both scholarly and pastoral, overlaid with a childlike affection for the simplicity of Christmas, and deep wonder at the Christkind lying in the manger. This Gospel, located after Matthew’s careful recitation of the Lord’s genealogy, tells the story of the birth of Christ from Joseph’s point of view. But here’s the first observation: you must remember it is told with hindsight. We know how the story ends, but we must enter into the narrative from the perspective of the righteous man, Joseph, who did not. It is interesting to consider two things about this passage. First of all, for us to know anything about the facts recounted, it is Joseph himself who must have told somebody. We are given a glimpse into the very soul of this great saint - how God speaks to him, and how he responds to God. It is a deep privilege - and a point of sober reflection from the outset - do we respond to God in this way? Does God speak to us in this way? If not - we must ask ourselves - why not? Secondly, an even more remarkable fact emerges, and I will make it boldly. There is a clear mirror image to the more famous Annunciation to Our Lady in Luke’s Gospel. This is deliberate - the narratives form a kind of diptych, where each complements the other from both parents’ points of view. But the information given to Joseph is arguably a more explicit reference to Christ’s divinity than what Gabriel said to Our Lady: i.e. that Our Lord is not simply blessed by God, and holy, but that he is in fact God incarnate. This means that a case can be made for saying that Joseph was the first human ever to receive the explicit confirmation that Jesus Christ is God. To understand that, you need a bit more background to the names involved. A key assumption of the Gospel writer is a Hebrew audience, one that knows who the Old Testament prototypes who previously bore those names. The famous Joseph of the Old Testament is of course the second to youngest son of Jacob and Rachel, favored by his father by a distinguished coat of many colors, much to the envy of his brothers, who first seek to kill him, and then sell him into slavery in Egypt. Joseph is also notable because God speaks to him in dreams - and his ability to interpret dreams is what really fires his siblings’ rage. The attributes of the Old-Testament Joseph thus informs our expectations of Mary’s husband. The overlays of Egypt are obvious - and when the time comes, this Joseph will flee with Mary and Jesus to the safety of exile in a foreign land, but it is no coincidence also that the (unnamed) Angel of the Lord speaks to his namesake in dreams, and he has the charism to interpret those dreams accurately. The Angel also tells Joseph what the child of the Holy Ghost’s name should be: Jesus - although, remember, “Jesus” is the Lord’s name in Latin. His name in Hebrew (or Aramaic) is ‘Yeshua’ - or Joshua. Matthew makes the point crystal clear: you shall call him Jesus because he will save his people from their sins. But wait. Why is that so obvious? What’s the reason for the ‘because’? Why is ‘Joshua’ such a self-evidently appropriate name? Well, the Old-Testament Joshua was the chosen successor of Moses, the one who ultimately defeated the Canaanites and brought Israel into the Promised Land, but the reason the name is perfect for the Lord is the key to the whole passage: the name (as I have mentioned a few times before) itself means ‘God saves’ - the Angel then says to Joseph: You shall call him ‘God saves’ because he will save his people from their sins. They are his people, he will save them, and only God can save people from sin. This is more than an implication - it is an explicit message for Joseph that the child is not only holy, but has the power to save his people from their sins: in no uncertain words: this child is God himself . Everything that Gabriel says to Our Lady is consonant with this. Gabriel tells her that the child to be born of the Holy Ghost is (a.) great, (b.) Son of the Most High, (c.) heir to the throne of David, (d.) holy, and (e.) Son of God. In that order. Of these, Son of the Most High, holy and Son of God are clearly direct messages of Christ’s divinity given to Mary. However, whilst we know that to be the case, because of subsequent events, the titles themselves are not as explicit as the information given to Joseph. Son of the Most High is a quotation of Psalm 82:6: I have said you are gods, and you are all sons of the Most High, and the line of Davidic kings are described as sons of God, in the sense of adoption. The difference with the message to Joseph is the explicit prophecy revealed to him that Jesus will save his people from their sins. It’s extraordinary! Joseph is given insight into what it means for the Virgin to conceive, according to Isaiah, what it means for God to be Emmanuel - with us. God is with us because he will save us from our sins. Just as the Old-Testament Joshua went into battle and led us to the Promised Land, so this child, to be born of Mary, will do battle with sin, and death, and lead us over the Jordan into Eternal Life. Remarkable, then, that Joseph’s reported speech is not part of the biblical canon. We know what God told him, we know his reasoning, and we know his actions, but we do not know his words. In that there is a lesson for all of us, and it is linked to the most important title he has: Joseph is a just man (or, a righteous man.) But being just does not mean you have to be right all the time. Joseph’s conclusion at finding the news that Mary is with child is more than just, it is supernaturally good. He had every right to divorce her with much fanfare, and preserve his own reputation. He chose to divorce her quietly, and take on her (supposed) guilt and shame himself. That’s why divorcing her quietly meant - everyone would conclude that the fault was with him, not her. But this supernaturally good decision was not correct - not for any deficit on Joseph’s part, but because God had not yet revealed to him the essential component: the child was of the Holy Ghost, and thus Mary was sinless. It is because Joseph is upright, honest, and just that he prays. He involves God in all his decision-making, and thus he has created space for God to speak to him in his dreams. If you want to be sure that you also do the will of God, you must be like him - you must create that space in the silence of your heart. Refrain from broadcasting what you think is the right answer, but instead, tell it to God in the quiet of your conscience, and the Lord, who speaks immediately to the just and upright of heart will respond. Let it be said of you, as of him: he did as the Angel of the Lord commanded him.

Like any great city, London has its idiosyncrasies, and the Underground is symbolic of the hectic busyness of the British capital. Thousands upon thousands crammed into its tiny tubes around corners so tight as barely to keep the cars on the rails. This means the stations are often built on curves with precipitous chasms between the cars and the platform edge: “ Mind the Gap ” the disembodied voice booms at you. I remember it every year at this time, (and not just because I love trains): it’s an excellent message for Advent. For Advent reminds us that you and I live in a very particular ‘gap’ - namely, between the First Coming of Christ, and the Second. The gap is the age of the Church, where we recognize that Christ, yesterday and tomorrow, the Alpha and Omega has come, and will come again. Pope Benedict XVI frequently used the delightful Italian aphorism: già, ma non ancora in his preaching on Advent. A phrase that means ‘already, but not yet' in English. It's Advent in a nutshell. As the Pope reminded us: The ‘already’ of the Kingdom that is present in the person of Jesus is a gift offered to us, but it is also a responsibility: the responsibility of cooperating with the work of God, of bearing witness to his Kingdom in the world. And this is the ‘not yet’—the journey, the pilgrimage of the Church through history, until the full manifestation of the Kingdom. We live in this tension, as if the cinematic reel were stuck between the frames. We know that Christ has come, but he seems delayed in his return. This leaves us with a profound spiritual instability that comes in the form of two temptations: the first, to assume we know everything about the Word that God has spoken, and the second, to imagine that God still owes us a different Word, a fuller explanation than he has already given. The balm for both temptations is to accept Mystery - to accept the otherness of God, and to have peace in not knowing all the answers, and in so doing we realize the spiritual instability is deliberate on God's part. But let’s deal with those temptations to unrest one by one, starting with the second: You may remember the postwar academic dream of a ‘ Theory of Everything' - one final equation from which the code of the whole universe could be mathematically derived. The late Professor Stephen Hawking once believed we were on the cusp of finding it, and that to find it would be to “know the mind of God” - and surpass it. Hawking was wrong. And by the turn of the Millennium he had the humility to admit it. As a student I remember watching him going about the city of Cambridge in those very days. I often wondered whether he was disappointed that his great hope had been dashed. He gave no evidence of it. But you see, it's undeniably true that Science has had to give up this grandiose claim, because (in layman's terms) the physics of the very small (Quantum Mechanics) and the physics of the very big (General Relativity) turned out to be fundamentally incompatible. You can follow one, or the other, but if you try and marry them together - you get nonsense. As scientific journalist, John Horgan, concluded: The universe is deeper and stranger than our minds—made, as the mystics say, in via negativa—can fully grasp. I don’t think we have yet come to terms with the consequences of this. Many people put their Faith in the progress of Science - many good people, ordinary people. It was almost an assumption that Religion would necessarily have to cede the high ground of Truth to the triumph of human reason. Not for nothing it entered our everyday speech - think for example of the rather impolite phrase: " it's not rocket science " - as if rocket science were unquestionably the pinnacle of human endeavor. However, the more we searched the mathematics for a new Word, the stranger it became. Ultimately, the Universe will keep its secrets, even from the greatest of minds, even from AI. The self-confidence of the giants of physics of the late Twentieth Century has now all but evaporated - but when we turn back to Religion for answers, we encounter the first temptation I mentioned, the temptation that since we already know everything there is to know about God’s Word, Religion has nothing to say. Responding to this incredible Post-War scientific optimism, Christian denominations have long been playing catch-up. Rather than proposing the Gospel as something radically new in every generation, we have been tempted to downplay Christ’s counter-cultural demands, and make both Christian worship, and Christian theology, accessible, and comprehensible. And ‘nice.’ But whilst there is a lot that’s good about accessibility and understanding - there is a grave danger of destroying Mystery in the process. Institutionally the Church has not caught up with the reality that Science is no longer proposing a Theory of Everything. Granted there have been no white flags raised from the laboratories, but a distinct lack of confidence in academia is noteworthy. Without most of us noticing, Science is, perhaps, on the cusp of returning to Mystery. It's time for us to regain our self-confidence in an age desperately seeking answers. You see, Mystery is not deceit, nor is it fairy tale. It is Truth shrouded in Wonder. Whilst we can never fully know the mind of God, we can know that He loves us, because He spoke the Word to us - and there is no further Word coming: Long ago God spoke to our ancestors in many and various ways by the prophets, but in these last days he has spoken to us by a Son. Heb 1:1-2 St. John Henry Newman is the prophet of Mystery. Having come to Faith in the crucible of Oxford, that great seat of reason, he recognized the inherent power that comes from believing in the name of the Son of God: “The most perfect Christian is he who has learned to live upon mysteries, to rejoice in mysteries, to look forward to mysteries.” So this is why we have Advent; with the Sanctuary stripped back, we carve out a space in our busy schedules to pause and reflect. To learn, and re-learn how to enter into Mystery. To put down the weapons of pride, and instead come to the manger-bed of Bethlehem, where the Lord who made the stars will soon lie gazing in wonder at them. Advent urges us not to fill that gap, but instead teaches us how to live in it. This gap is not a wound, nor a mistake, nor a void; it’s a pilgrimage into Truth.