The Perfection of Faith

Rev. Michael J.V. Clark • August 9, 2025

“To live is to change; to be perfect is to have changed often.”

Newman’s provocative insight reveals that if we don’t change, we’re not living. A fish that stops swimming is in fact going backwards - but we don’t just want to live, we should want to become saints. But there’s an inbuilt opposition to that growth. You see, man cannot achieve his ultimate goal using his own reason, or under his own power. It’s like the deliberate imperfections of aerodynamics; the instability that permits a plane to fly.

This frustration is what makes us fundamentally religious: we seek answers to big questions outside of ourselves, rather than within. But you see openness to growth is what the virtue of Faith looks like in a concrete way. Why? Because the virtues are the way we chart the operation of God’s grace in our lives. It’s how we measure whether we’re maturing spiritually or not. Faith is, as the Letter to the Hebrews defines it:

“The assurance of things hoped for; the conviction of things unseen.”

Heb 11:1

The problem with this is we use the word, ‘Faith,’ to describe different things. Here, the Bible is talking specifically about the theological virtue of Faith, which is infused by grace. But all that goes way over our heads if we can’t define what a virtue is, nor what grace is.

Let’s start with the virtues. What we call a virtue is a character or quality that disposes a person to morally good acts. We work out what they are by examining our behavior, and the behavior of others, synthesizing the principles for good living, and putting a label on it. According to Catholic thought, building upon the foundations of Aristotle, we can distill four ‘cardinal’ virtues, that can be known by reason, and on top of these we have three ‘theological’ virtues that God has revealed to us in the Scriptures.

The cardinal virtues are prudence, justice, fortitude, and temperance, and each of these represents a ‘golden mean’ on a sliding scale between two other characteristics: one of which is an excess, the other a deficiency; and both of which are vices. The golden mean does not necessarily sit in the center between the two - it can be skewed more one way, or another. So:

- Prudence sits between Cunning, and Recklessness

- Justice sits between Rigidity, and Laxity

- Fortitude sits between Foolhardiness, and Cowardice

- Temperance sits between Austerity, and Licentiousness

These natural virtues can be discerned by thinking logically and carefully, and they apply to all men, for all time. But they are very, very hard to achieve, and there is a gap at the end of the day. If you practice these virtues, you may be good, but you won’t be perfect. Indeed, you cannot be perfect.

To be perfect, requires God’s intervention - and we call that grace. Here’s where the three theological virtues come in. They are:

- Faith

- Hope

- Love

You already know where these come from. I suspect the majority of you who are married will have heard the verse at your weddings:

“So now faith, hope, and love abide, these three; but the greatest of these is love.”

1 Cor 13:13

The theological virtues don’t operate like the natural virtues. They don’t sit on a sliding scale, because each of them is given as a gift from God. They do, however, interact with the natural virtues. In fact, in individual circumstances they alter the golden mean, moving the needle in one direction, or another. It is the operation of the theological virtues that changes us from being good to being perfect, or, to think of it another way, by grace we can be made saints.

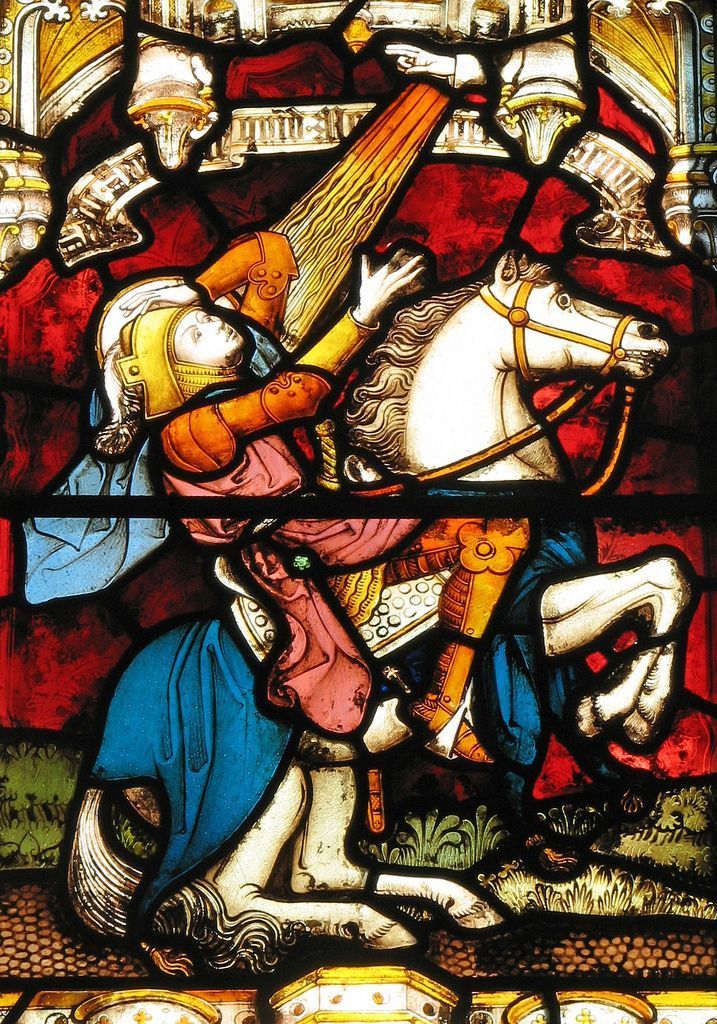

The Letter to the Hebrews gives eleven examples of men and women through salvation history that did something different because of the virtue of Faith. God’s action in their lives shifted the needle and they made choices they otherwise would not have made, because they recognized, by Faith, who it was that was doing the asking.

What is true of Faith, is also true of the other two theological virtues, so let’s see how they interact with the natural virtues. Let’s take Fortitude, the mean between Cowardice and Foolhardiness. Faith moves the needle in the direction of Foolhardiness - it makes us do things against the odds, or against the evidence, because we believe God and trust His commands. An excellent example is Peter’s encounter with the Lord walking on the waters: Peter’s Faith overrides his caution, and since it is the Lord who bids him come, he comes - until of course his Faith fails, and he sinks into the waves.

So let’s take another example of Temperance, the mean between Austerity and Licentiousness. The theological virtue of Love may move the needle in the direction of Austerity in specific cases. Think, for example, of the commitment of Carthusians, or Trappists, or hermits, they eschew not just luxury, but even basic human goods. They would not be exercizing the natural virtue of Temperance, except that Love, for Christ, and the salvation of souls, requests it of them - and if it is done out of Love (and not for other motives) the virtue is perfected by being changed.

We have not mentioned Hope yet, which is the confidence that what God promises will in fact be fulfilled. Taking the natural virtue of Justice, we might observe that Hope asks us to move in favor of Laxity - taking a longer view, and showing mercy, rather than requiring a strict application of law in the here and now. How often do parents exercise this quality! A brilliant example is Our Lady at Cana when she says “do whatever he tells you” to the servants. Her Hope modifies what Justice requires, which would be the honest admission that the wine has run out.

So at the heart of the virtuous life is openness to grace. It challenges our nature, and expands our horizon from the topical to the eternal. With the intellect and will that we have by nature, it is possible to be good, but for most of us the report card is mixed. By grace, it becomes possible for us to be perfect - and that works by showing us a deeper logic - the logic best expressed by Christ’s self-sacrificial love on the Cross. This is my body given up for you. Just like the other examples, Christ’s gift of himself on Calvary moves the needle of virtue. Don’t settle for being good enough - be perfect, as your heavenly Father is perfect.

Recent Posts