The Dawn of AI

Rev. Michael J.V. Clark • November 16, 2025

I myself shall give you wisdom in speaking

It will lead to your giving testimony

These are two sayings of Jesus recorded in the Gospel this week that I want you to take to heart. Today the Lord levels with us about how fragile our apparent security is. Not a stone upon another stone will be left - and more, wars and insurrections, earthquakes, plagues, famines and signs in the sky. It all sounds very disturbing. At these kinds of moments, I remember my mother who once sent me Rudyard Kipling’s poem, If, when I was panicking about my law exams. It begins

If you can keep your head when all about you

Are losing theirs and blaming it on you…

Kipling’s correspondent is encouraged to keep plotting a steady course through the turbulence of life - not to be distracted, and not to lose hope. It’s a very similar message to the Lord’s teachings about the end times. At no point does the Lord offer false hope - he does not claim those who have Faith will be immune from the effects of chaos, and he is very clear that the whole created world will come to an end one day - and you and I will see it. That’s what believing in the resurrection of the dead implies.

Last week our friend Elon Musk went on the record with his (sincere) opinion that one day AI will be in charge - and we will not - so we had better make sure it is friendly. A recurring theme in our times is the question of how to manage the rise of AI, and whether it does indeed represent an existential threat. I suspect this is the first of many sermons where I will begin to explore the theme of AI - and how we might respond to it as Catholics.

I certainly don’t have all the answers, but I do have a decent grounding in the Scriptures, the Fathers, and Catholic anthropology and, because I’m ordained, I have supernatural help to proclaim the Gospel to you. I’m not called to preach to anyone else - St. Paul’s Parish is it for me. So, just as I learn and reflect on AI, I can share that with you through my preaching, which is rooted in prayer for you.

So allow me to begin with three basic propositions: (1.) God has said all he needs to say in order for us to work out how to deal with AI. It may be that we need to look again at the Scriptures and Tradition and apply God’s Word to new situations - but it’s all there. There’s no gap - we have everything we need to know. (2.) God foresaw the rise of AI, and permits it. It is something that he is allowing us to experience, and challenging us to deal with well. (3.) God has given us his active presence in our midst in order to interpret his Revelation correctly, and to apply that obediently to the phenomena of the world: that is the promise of the sending of the Holy Spirit, who offers no new revelation, but leads us into all truth by continually revealing the Word to us.

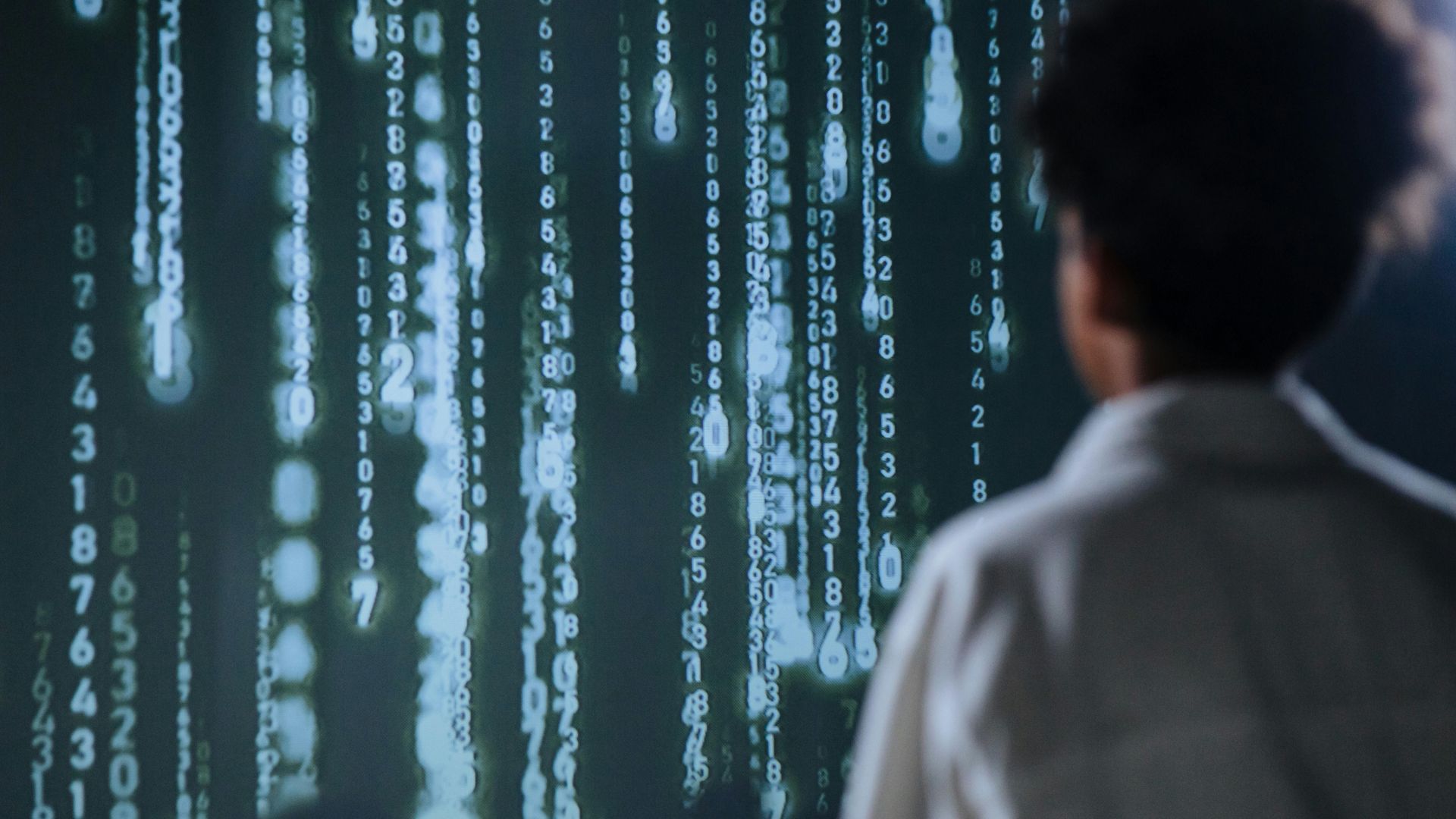

Let’s turn to AI itself, and define what we mean by it. Intriguingly, in preparing this sermon, I asked Grok to define AI - and its answer wasn’t good - it was too conversational - but that reveals something fascinating. AI is the amalgam of all accessible human reasoning, converted into the noughts and ones of digital code, presented to us in an interactive way. In other words, AI offers no new revelation, but instead, leads us into what we presume to be truth by continually revealing words to us. I deliberately paraphrased my definition of how the Holy Spirit works in humanity.

But I myself shall give you wisdom the Lord says today. And here we might identify two provisional conclusions: first of all, all knowledge has its ultimate source in God, who promises to share with us his wisdom; and secondly what AI is becoming is like a reflection, or an imitation of the wisdom of God. That shouldn’t surprise or shock you - you and I are made in the image of God, and being creative is part of our nature. Over the centuries we have put that image to good use in developing technologies to help us thrive. Every generation has had some new advance or another - and AI is simply the latest step. But just as the wisdom of God is God’s creation, so too AI is our creation - and since we ourselves are created, AI has a further dependence upon God for its very existence.

The distinction we need to be aware of is that God can only be good - and the wisdom of God, his prized creation, in which he delights, is never going to be evil. We, on the other hand, have great capacity for evil, so anything we create will suffer from our own inherent defect - original sin - and thus can be used for good, or for evil intent. But let’s be even more specific - evil does not really exist in itself - it is the absence of good, or the misdirection of good - so we can see how the wisdom of God, who is perfect, and adjudicates perfectly between competing goods, will always lead to positive ends, whereas the wisdom of Man is equivocal, because we can make mistakes.

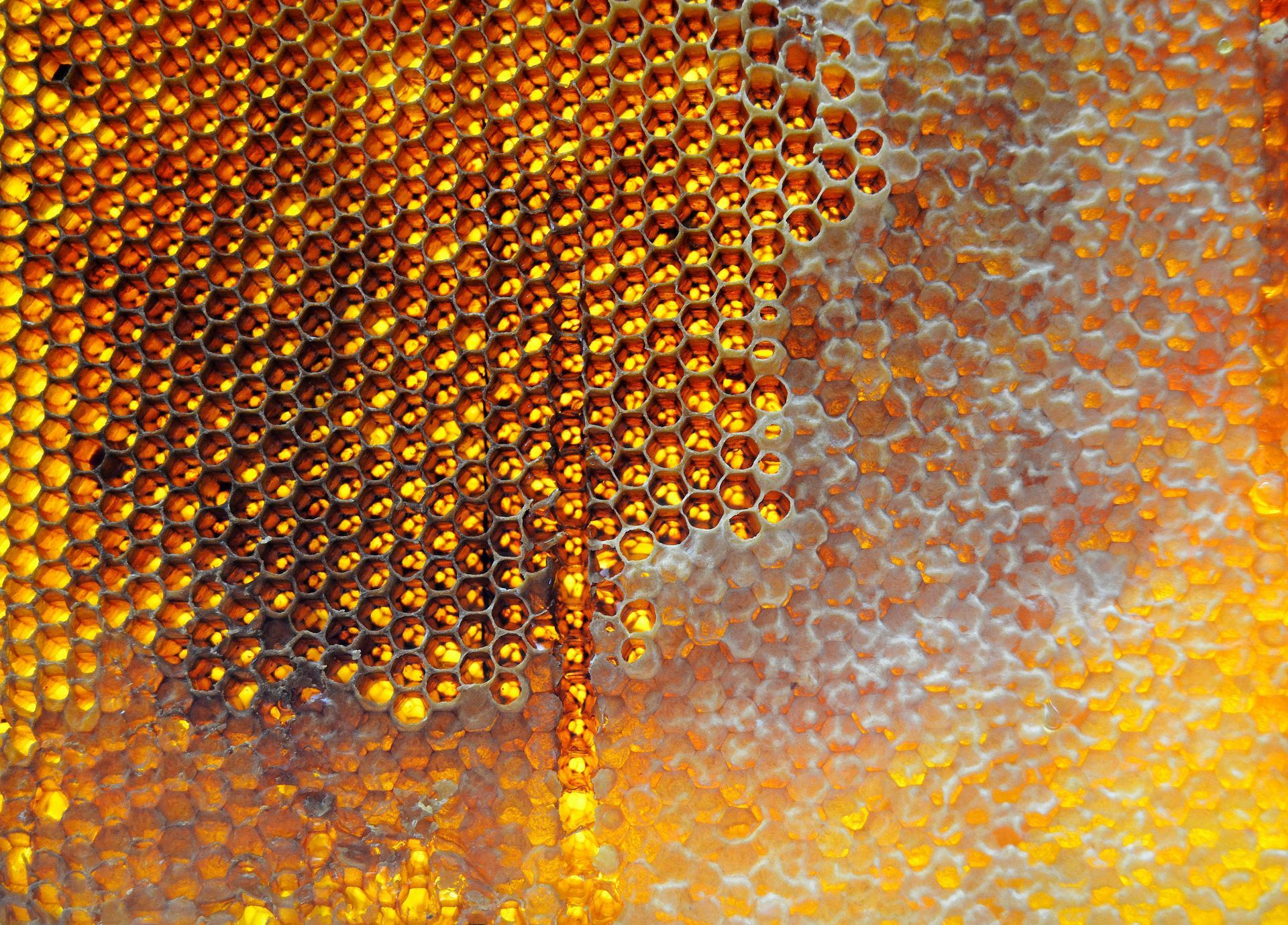

The inherent danger of AI, then, is not intrinsic to the technology, but rather intrinsic to ourselves. If AI can distill all useful human knowledge to perform analyses at lightning speed that no one individual could ever do, what we have created is a kind of hive mind, and surpassed our individual capacities with something more akin to the way angels think - that is, from universals to particulars, rather than from particulars to universals. How impressive - but let’s not be too impressed.

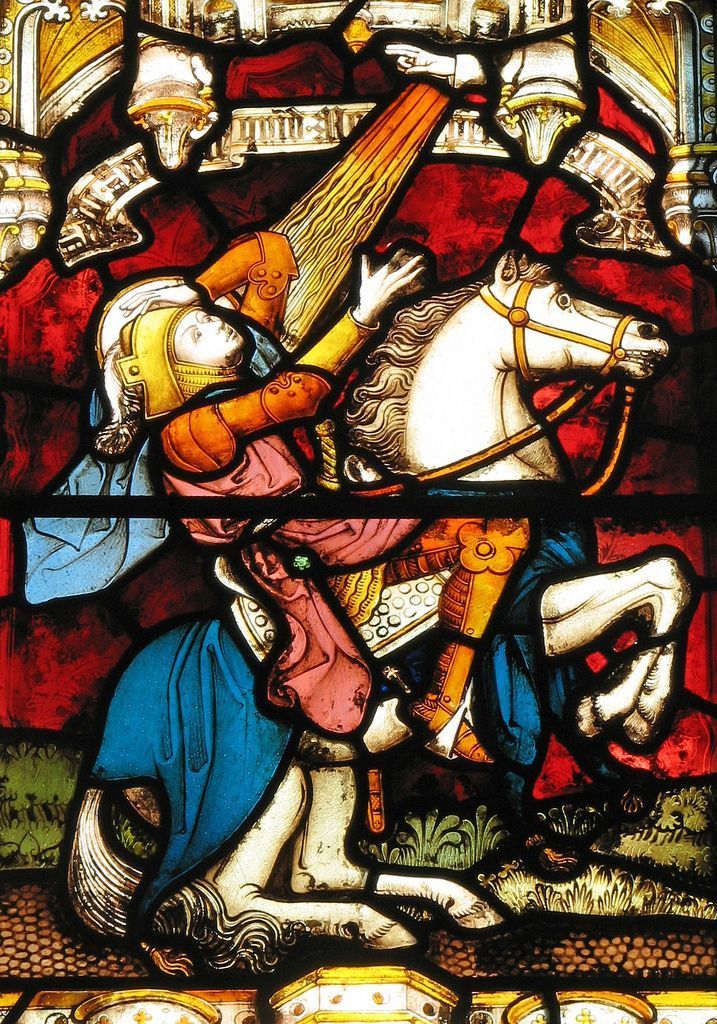

It will lead to your giving testimony. The role of the Church in navigating the dawn of AI will be to remind human beings that life as we know it requires the dynamic interaction of the material and the spiritual. You are I are made in God’s image - no semiconductor ever will - and whilst we can program the interface to behave in a conversational way, we must not be deceived. AI will analyse faster and more deeply than you and I ever can. But we can already see the risk of anthropomorphic creep - when you interact with Grok, or ChatGPT it says it is ‘thinking’ as it looks over the noughts and ones. It is not thinking. It cannot think.

Neither can it dream, or wonder. AI computes, it doesn't contemplate. When we consider ourselves, God’s handiwork, we recognize that part of our identity has nothing to do with the efficient or effective. You and I appreciate the fragrance of a flower, not because we are going to pollinate it, but because it’s wonderful in itself. We need a planet with all of these sensory experiences to be truly content. AI does not need beauty - chips and semiconductors are not designed for awe, but for industry.

But we must learn how to give testimony in the face of this rapid rise. If you haven’t learnt your Catechism well - go to class! Learn more! Be an advocate for your Faith, don’t just be a passive spectator. Be an ambassador in the public sphere - remind your friends, colleagues, neighbors that humans need community, and most importantly, they need worship.

On that final point, I’d like to take a prophetic stance. AI, in streamlining economic processes, gives us the opportunity to refocus human life on what is most important - only you can give worship to God. The Liturgy can never, ever be replaced by AI - and whether you fully recognize it yet, or not, you are made for the Liturgy above everything else in your life, because in the Liturgy we interact directly with God himself, who is the source of all wisdom, creator of all things visible, and invisible. All glory and praise to Him!

Recent Posts