Pride Before Fall

Rev. Michael J.V. Clark • October 30, 2025

Driving around the back lanes is a delight this time of year on a sunny day. The dappled light filters through leaves ablaze in fiery hues, even when the fall foliage isn’t quite as spectacular as it is some years. It’s a vision that attracts us—only the truly oblivious could fail to be delighted. But we perceive a change, and our delight is twinged with anxiety. It is hard-wired within us. I mean that literally. Have you ever noticed there’s a distinct earthy odor after it rains? It’s kind of pleasing, and it even has a name—it’s called petrichor, and humans in fact have better acumen for petrichor than sharks do for blood. You see, we are meant to observe the changes of the seasons with high specificity.

As C.S. Lewis knew, this seasonal ache is more than whimsy—it’s God’s whisper of a farther country, where leaves fall no more, but the trees are always green and laden with fruit. He recalled this insight when reading the children’s author, Beatrix Potter’s exquisite story, Squirrel Nutkin: “one autumn, when the nuts were ripe and the hazel leaves golden” it begins. This innocent tale pierced Lewis’s heart, awakening in him "a certain quality of sensation, or quality of awareness,” perhaps a longing for the eternal amid the sylvan glade.

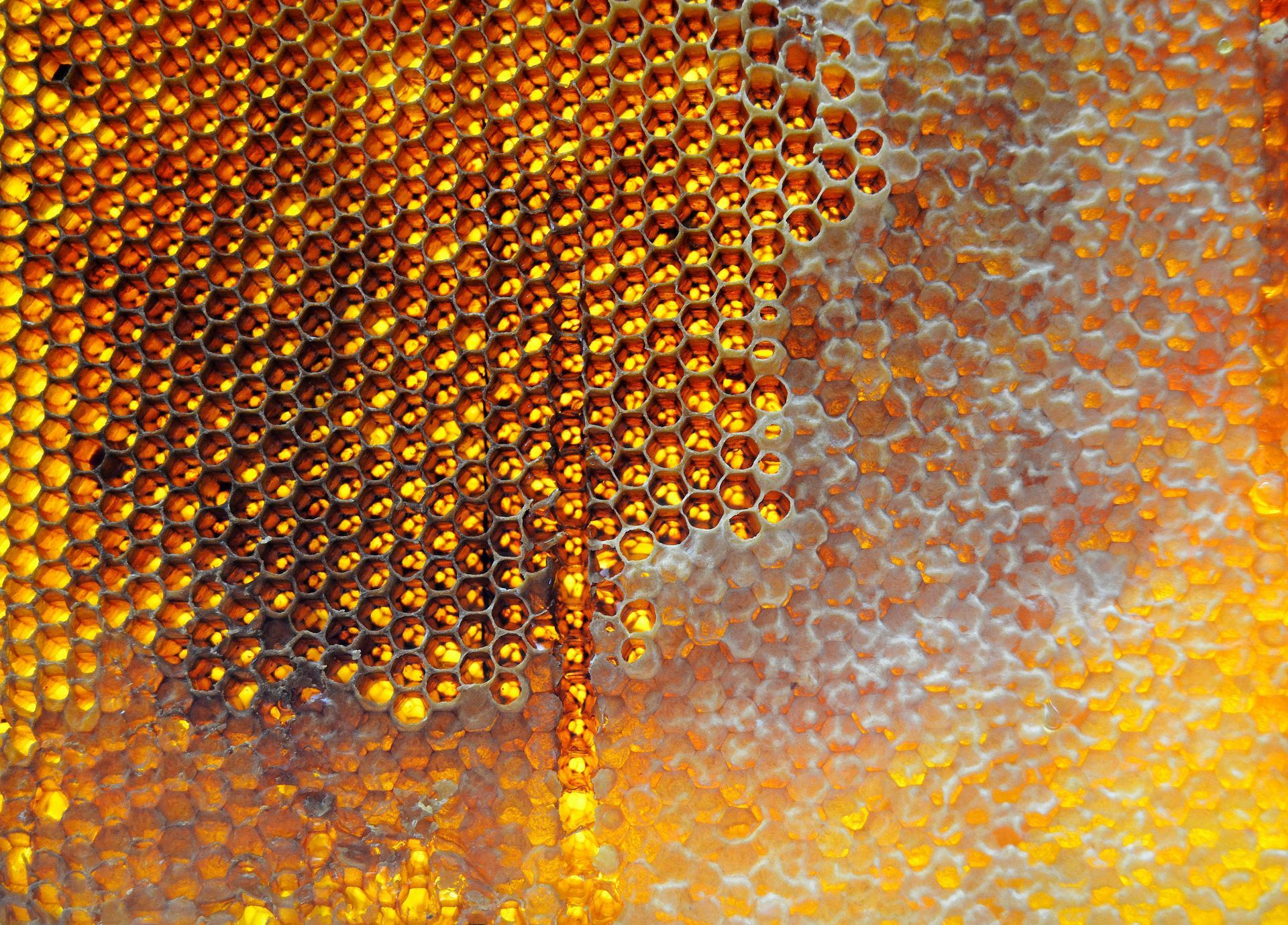

Our anxiety at this time of year stems from the fact that when we see the leaves turn, and smell the earthy notes from the ground after rain, we know we need to prepare for winter. The frost is coming, and food will be scarce. We need shelter, and warmth, to make it through the shortening days. We could rely on our intellect, to store up food and fuel, but we also need luck. Such is biological life—and while we check the weather, put on extra layers, and stock up with provisions on a daily basis—it’s easy to neglect the spirit at these times. To forget that preserving the body at all costs is not the meaning of life, after all.

But while the Cosmos is giving us signs that we need to slow down, and be prepared, our sophisticated modern society has decided the opposite is, in fact, in order. I don’t know about you, but my diary has exploded in recent weeks—between now and Thanksgiving, it’s an endless procession of meetings, dinners, and galas. All the rest of Creation has taken the hint: the animals are busy preparing for the winter. The roses are putting on their rather feeble last blooms, and the leaves are shedding from the trees. But mankind? Oh no. We’re better than all that. If there was ever evidence for the expulsion from the Garden of Eden, it is this! Lewis warns:

“We are half-hearted creatures, fooling about with drink and sex and ambition when infinite joy is offered us”

We mistake our frantic calendars for freedom, without realizing we exchanged leisure for toil when our first parents chose to exalt ourselves over God.

There are two further conclusions we can draw from the changing of the seasons that are helpful for the spiritual life: first, that the same God who encourages the fresh green growth of Spring now commands the trees to loose their grip, become translucent, and fail; and secondly, that in losing that vigor, light is able to penetrate to the roots. Have you ever noticed that it is easier to see further, and more clearly, in the woods in winter? The undulations of the landscape are obscured by the flush of greenery, but they are now revealed. We can see the contours—the crags, the ravines—which otherwise lie in wait under a carpet of briars.

God permits the vigor of youth, but demands the fall as well. We should not refuse it, or protest. If our understanding of success is only a tree in full leaf, full of sap, and green, then we haven’t yet grasped the way God seeks to save us. He asks us to humble ourselves, to be receptive to grace, and open to the change in us that can only happen when we put our pride in check. It’s particularly satisfying to note that our word, humble comes from the same root as soil, or earth. To have humility is to be full of humus—of the soil of repentance.

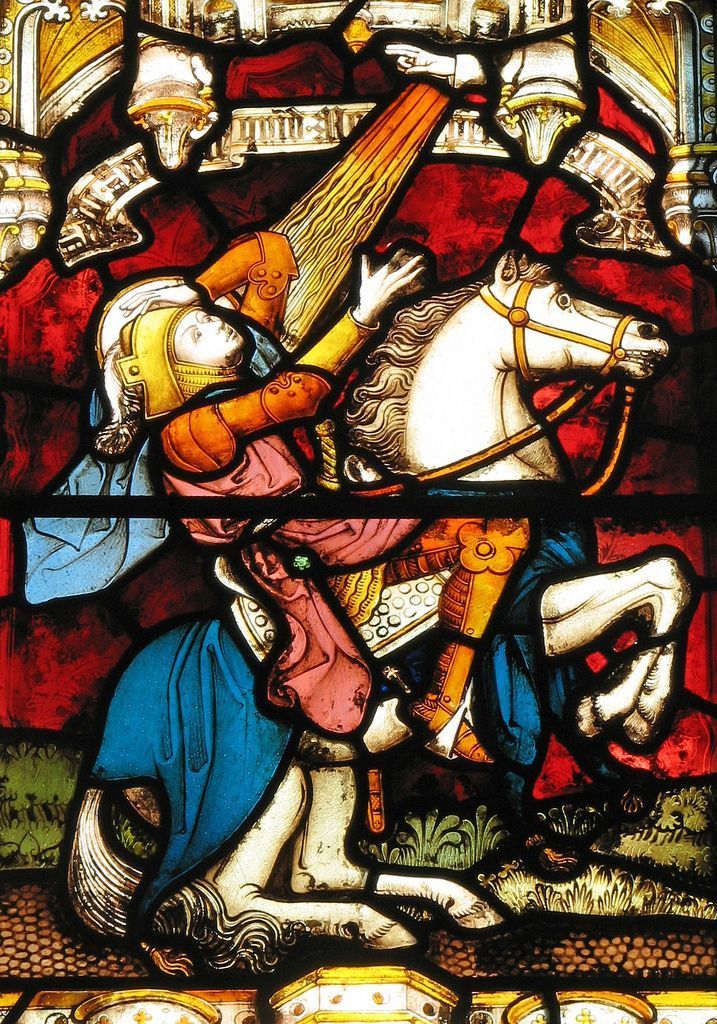

In the Gospel today, we see this dichotomy very clearly. Both the Pharisee and the Publican know that God is who He says He is. He is Almighty, and eternal. They both desire a relationship with Him, but the Pharisee has concluded that if he does all the outward things the law requires, then God will thank him. As St. John Henry Newman observes in his sermon on this very parable, the Pharisee "looked upon himself with great complacency, for the very reason that the standard was so low, and the range so narrow, which he assigned to his duties towards God and man... He thanked God he was a Pharisee, and not a penitent."

The Publican, meanwhile, recognizes that in all his efforts he falls short, and simply begs God for mercy, without seeking to justify himself: "O God, be merciful to me, a sinner." In truth, in God’s sight, no man living is justified—justification is the consequence of accepting the need for grace—that I cannot be saved by going through the motions. Like the trees that accept being denuded by the wind, we too must allow our pride to be stripped away, revealing the skeletal form of the trunk with all its knots, gnarls, false starts, and crossing branches.

Newman captures this poverty of spirit that opens us to joy: "That poverty is a state of utter need and dependence on God. It is the poverty of the publican who begs God for mercy, as opposed to the plenty of the Pharisee whose prayer is a celebration of himself." Such self-emptying, Newman insists, "is the very badge and token of the servant of Christ.” Not for nothing, Adam and Eve used leaves to clothe their nakedness - but in so doing, set up a barrier for grace. God requires us to be reclothed, and for grace to hit the soil again.

However, before we chastise ourselves too much, our transcendence of the changing seasons also has a positive side. It means that we know the soul is unmoved by the winter wind. We already live half in time, half in eternity, and we should not fear whatever assails the body, only what kills the soul.

In Eden we were led by the spirit. In disobedience to God, we exchanged that for being led by the body. We toil for our food, and go hungry, just like the beasts, whereas God did not design it this way. We were meant to have all we wanted for no labor whatsoever. Instead, we chose the long way back to God, but out of the dust and clay, God pursues us in Christ. All was not lost, because one woman said yes to a new Creation, of which we see only the first rays of dawn. For when we fall and turn to dust, then we can rise again. The light that hits the ground when our pride falls like the leaf litter enables a Savior to rise up from within our midst, a Savior who is Christ, and Lord.

Recent Posts