Take up your Cross?

Rev. Michael J.V. Clark • September 15, 2025

The Bible is stranger than you think. Phrases like “there’s nothing new under the sun,” or, “the writing is on the wall,” or, “by the skin of your teeth” are so common, many do not even realize they are quoting Scripture. But there is a risk with such familiarity we assume we know what they mean, missing their profound and shocking depth.

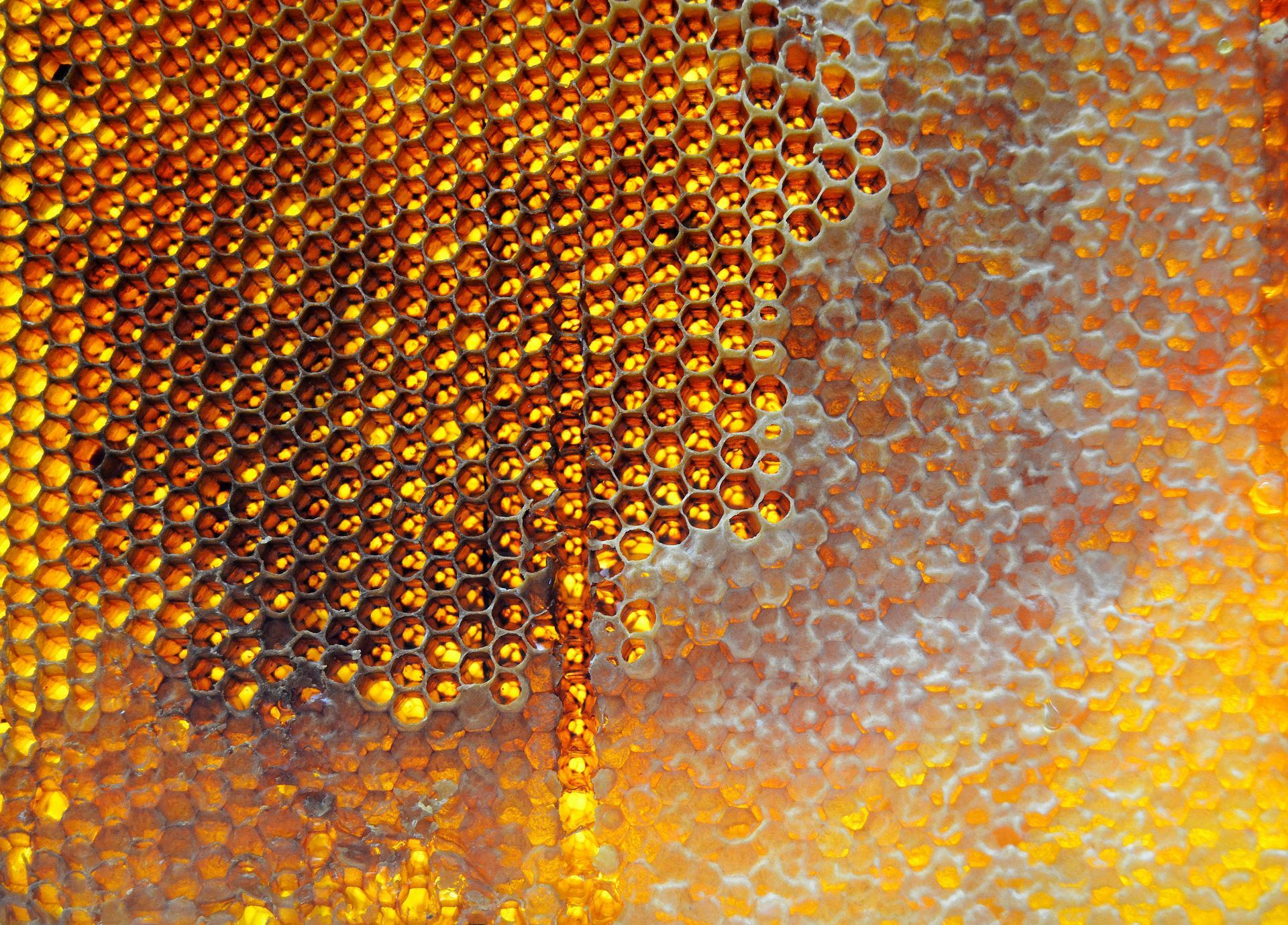

Take the image of the Cross, for example: a symbol we rightly cherish [as an aside - I hope all of you have a Cross hanging somewhere in your home (ideally, even more than one…] It gives us hope, and models for us the power Christ has over the things that we fear the most: suffering, and death. But our familiarity has almost anaesthetized us to its infinite cost - and the paradox in finding comfort through the invitation to sacrifice.

Have you ever considered for a moment how odd it is, that we should find hope and healing in an image of a man, slowly asphyxiating, in terrible agony? Whilst it should never be frightening to us, the image of the Cross is certainly challenging - and when we gaze upon it, we shouldn’t let that strangeness pass us by. It is a sign of hope, for sure, but also an invitation. This is the way that we too must pass, if we are to have eternal life: "the Son of man must be lifted up" - and when he is lifted up from the earth, he "will draw all people" to himself.

Five times in the Scriptures Jesus commands his followers: “take up your Cross.” This, too, is an extraordinary thing to say. We often interpret this kind of cross as the little burdens and trials we endure in life - the things that grind, or annoy us. That’s not wrong, but it’s not sufficient. We don’t often think of embracing the ultimate sacrifice in defense of Truth. Perhaps we should?

But there’s actually a little more nuance to the invitation: ‘take up your Cross.’ The Greek word for ‘Cross,’ σταυρός, (pronounced ‘stafros’) almost universally means the cross of crucifixion nowadays. But it didn’t originally. In human terms, the word is quite a primitive one: it describes the kind of sharpened pole that humans have been fashioning for thousands of years; to create structures, such as fences; or weapons, such as spears. You can see the evidence of this in the English words, ‘staff,’ or ‘stave,’ which come from the same Indo-European root as σταυρός.

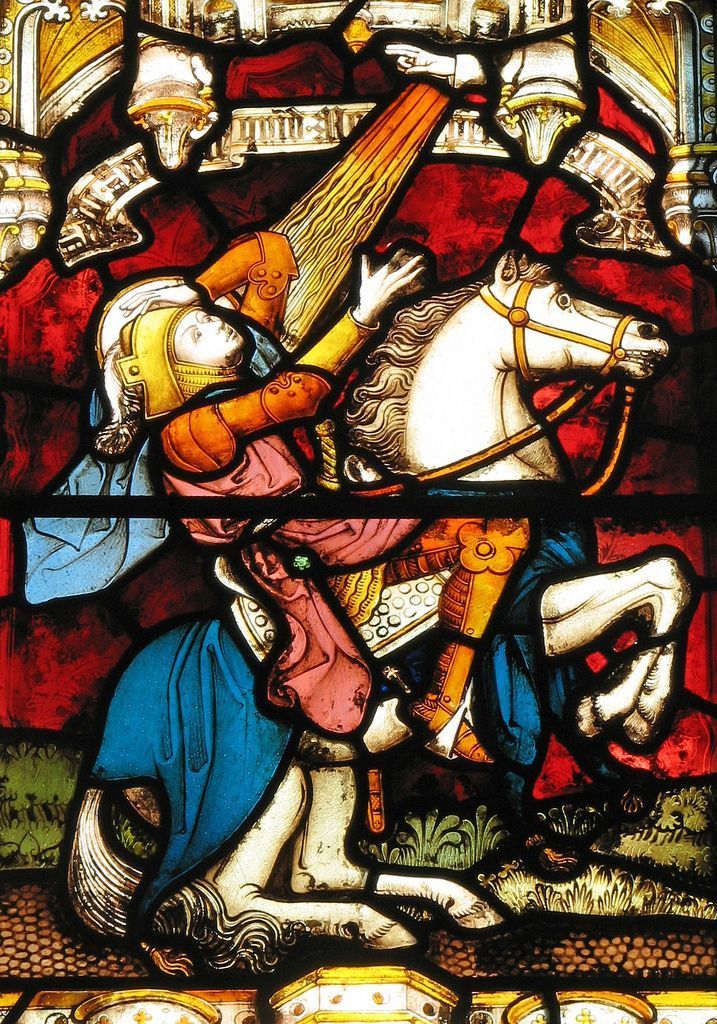

So when Jesus says, ‘take up your Cross’ there is a deliberate ambiguity in his meaning. Yes, it certainly can mean ‘be prepared to suffer death,’ but the invitation was made before the events of the Crucifixion took place. No-one (except Jesus) knew how the story would end. Equally well, ‘take up your Cross’ could mean take up your staff, an allusion to Exodus 12 and the instruction to the Israelites to eat the Passover meal with loins girt and staff in hand - but it can also, equally well, mean take up your spear - as in, a weapon - and be ready for battle.

Of course Christ means all three, at the same time, but the original hearers would no doubt have selected which meaning suited them best. Only after Calvary would the primary meaning become a definitive call - and the other possible meanings make sense by reference to the first: the Cross is the direction of travel for all Christians - and in so doing, we enter into the true Passover, crossing the Red Sea from death to life, staff in hand, and also fight valiantly against evil with the only defensive weapon possible: the life-giving Cross of Christ. It urges us to live courageously, aligning our lives with Christ’s radical demands, not to soften it, or neatly package it up so it fits into a space we’re comfortable with.

The centrality of the Cross is emblematic of Christian initiation - we are baptized, and anointed in the shape of the Cross. From that moment onwards, we trace that Sign over our bodies with water to remind us of our acceptance of Christ’s call. It’s no wonder, then, that the Cross forms the centerpiece of the great Christological paean found in Philippians 2:6-11. You may be very familiar with it - but again, it is stranger than it first seems.

Scholars have long tarried over these words, because they don’t quite seem to fit into the structure or vocabulary of Paul’s letters. We know Philippians was written by Paul from prison, probably in Rome, and if so, between AD 60 and 62. But these lines have a distinctive meter and alliteration, which suggests they were designed to be learnt by heart and recited by a group. They are, if you like, a form of Creed, and written to be sung.

It seems very likely that Paul didn’t write them. He is quoting a text that already existed - and that makes it very old, indeed - some of the oldest words of the New Testament, possibly emanating from the original Jerusalem Church, far older than the Gospels, and vying only with snippets in Paul’s other letters for the title of the oldest surviving Christian text.

The text has a mirror-image structure, that forms one half of the letter X, or chi in Greek - for this reason we say it has chiastic form - it paints a landscape, in words, of descent and ascent, where the lowest point is death on a Cross, whence God raises Christ up, and exalts him, commanding us to revere his name for all eternity. It would be the perfect chant to sing during Baptism, where the text (and music) descends into death and rises to new life - and indeed, that is probably what we are looking at - whoever knew there would be archaeology, hiding in plain sight, in the middle of Paul’s letters?

In this hymn, we can see what was important to the very first Christians - the ones who were alive, and witnessed, the events we commemorate every time we celebrate Mass - and what was of central importance to them was binding themselves to the image of the Cross, imprinting it on their lives - and if it was so important to them that this text survives intact to be proclaimed 2000 years later in Greenwich, CT, then it is still important to us now.

Recent Posts