The Rich Samaritan

Rev. Michael J.V. Clark • July 26, 2025

“No-one would remember the Good Samaritan if he’d only had good intentions - he had money as well.”

Jesus uses parables to explain deep truths - things that we need to mull over for a long time; things we need to keep coming back to. The word means to throw alongside - it’s the same root as the ‘parabolic’ in a parabolic curve - the kind you don’t want to see in your 401k. You could think of it as a boomerang - instead of giving a direct answer that you might forget, the Lord paints a vivid picture with a memorable story, so you can keep returning to the ideas again, and again. It’s the perfect strategy. But there’s a risk.

Parables, you see, have multiple layers. There’s a superficial reading, perhaps one or two slightly deeper readings, and then there’s the core teaching, which makes all the little details in the story sparkle like diamonds. Only then can you say you have received what the Lord wished to convey. So let me disavow you of the superficial interpretation: the moral of the story is not simply: “be kind to people in need” - that is the most basic teaching, and does not need a parable to convince you of its suitability. Indeed, the Lord teaches this directly on multiple occasions: e.g. “love one another, as I have loved you.” It’s not about being kind.

So what is it about?

Well, to understand a parable, you need to pick it apart, and see the details. There are many, but let us concentrate on a handful:

The traveler’s direction: from Jerusalem to Jericho

The traveler is described as “a certain man” - anthropós tís

The Samaritan is wealthy and generous

He uses oil and wine to minister to him

He takes him to an Inn

He gives two denarii.

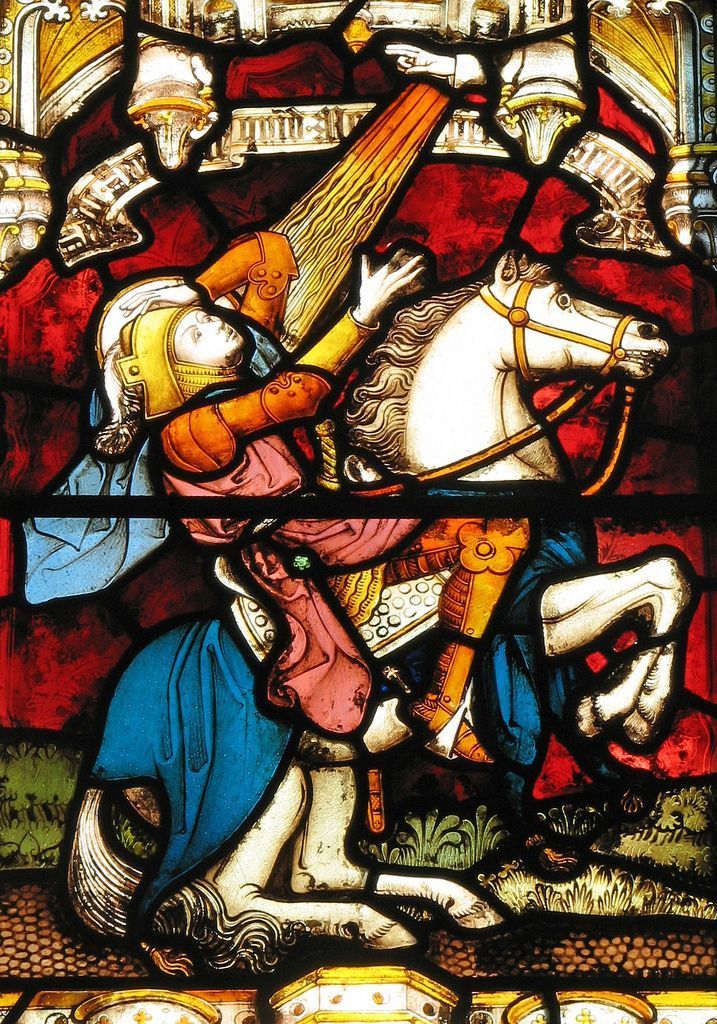

He will return

The traveler’s direction is important. Although a journey of merely 18 miles, it involves a descent of 3439 feet to the lowest city on Earth. Jericho is 864 feet below sea level, whereas Jerusalem is on a high mountain. Jericho, in this sense, represents hell - the bowels of the Earth. Man has turned his back on Jerusalem, where the presence of God tabernacles among men, and instead is journeying into the pit. He’s going the wrong way - and thus the victim is not entirely innocent. He is in a bad place because of his previous bad choices.

The Greek word for man here is very broad. Almost every interpretation of this parable assumes that the man going to Jericho is a Jew - and therefore the parable is all about Jews receiving mercy from their despised enemies, the Samaritans. That is there by implication - remember there are multiple layers of meaning - but to conclude this about the parable you have subconsciously imported a detail which is not explicitly there. The parable takes on a very different vibe if the robber’s victim was also a Samaritan, doesn’t it? Who’s to say he isn’t? The Lord just tells us it was a certain man - an everyman. The robber’s victim is you - and me.

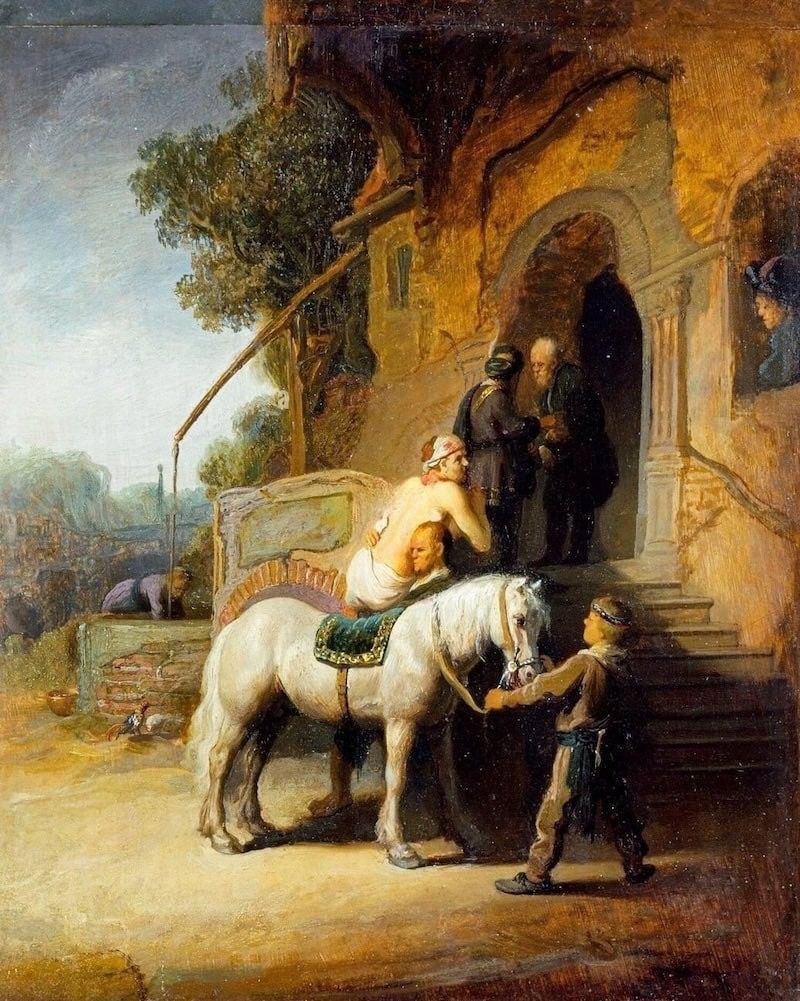

The Samaritan represents someone who is entirely different from us - he is not our friend. He is a foreigner in this land - and he is extraordinarily generous and wealthy. The quotation I began with is from the late Margaret Thatcher, quondam Prime Minister of the United Kingdom. She was manipulating the parable to make a different point - that wealth generation enables us to be charitable. She’s not entirely wrong there, but she misses the point. We don’t actually know why the Samaritan is wealthy - we’re not told he is hard working - it’s just supremely obvious he is able to flash the cash however he chooses.

Note carefully the mention of tending the victim’s wounds with oil and wine. What does that remind you of? Who else do you know of that uses oil, and wine, to heal people’s wounds? Maybe the picture is becoming clearer…but let’s move on.

Next, the Samaritan uses his beast (redolent of the Sacrifice of Isaac on Mount Moriah) to take the victim to an Inn. This is not an irrelevant detail. I have told you before whenever you come across a ‘hapax legomenon’ - a word that is only used once in the Bible - it should scream out at you. Here is such a feature - the word, pandokíon is only found here in Luke’s Gospel. It is a construction from the word pas, meaning ‘all,’ and dechomi, which is the verb to receive. The Samaritan, having tended to the victim’s wounds with oil and wine, takes him personally to a place that receives all. What kind of a place might that be?

The Samaritan, we are told, cannot stay with the victim. He must go away, but he tells the innkeeper he will return, and gives him two denarii to cover expenses. Again, the two denarii are important. A denarius was a single Roman coin. It represents a day’s wages, and thus symbolically, a day. The Samaritan is the one who makes arrangements for two days only. He must return on the third day.

I hope by now the details are coming together to give an accurate picture of who the Samaritan is. It is, of course, Christ himself, and the parable is all about man’s need to receiving the healing that only he can provide and only he can pay for. As St. Teresa of Calcutta once said to a wealthy donor: God has lots of money. But the Samaritan has a place to take us - an Inn, which receives all, and is staffed by people he entrusts to look after us until he returns. This Inn is, of course, the Church. Only here can the oil and wine of Christ’s Sacraments be administered with his authority to raise us up when we find ourselves half-dead on the road to hell.

Margaret Thatcher was right that the Samaritan had both good intentions, and resources, but she failed to spot the sting in the tail. The Lord says at the end: ‘go, and do likewise.’ This is impossible. No-one has the purity of intention or abundance of resources to do what the Samaritan does. Oh no. Instead, ‘go, and do likewise’ is an invitation to assist him in doing it.

Only he will not pass by on the other side; only he will move towards the victim who got himself into a mess by turning away from God; only he has the oil and wine; only he will return on the third day. But there’s a final question. When the Samaritan goes away for three days, where is he going? Well, since man had set out on the road to hell, someone had to complete the journey. The Samaritan is the only one who could go to hell…and back.

Recent Posts